Laikipia, Kenya

This month, in broad daylight on our Kenyan farm, a lioness mauled one of my bull calves. Before she could make a kill, a quick-witted herder intervened and drove the beast off. My son Rider loaded the injured calf into the pickup and brought it home, where he gently cleaned the tooth and claw wounds, then injected the poor creature with antibiotics and a painkiller. Big cat injuries go bad fast, but we all felt cheered that the calf, to my mind a future champion Boran bull, had survived and might pull through. The next morning the calf got to his feet and suckled his mother. What a sight that was. The morning after that, the mother was out grazing with her calf when she inadvertently bashed into a tree in which hung a beehive. The African bees, now angry, poured out of the hive and stung the injured calf to death. Rider was quite emotional about it. Life out here can be harsh.

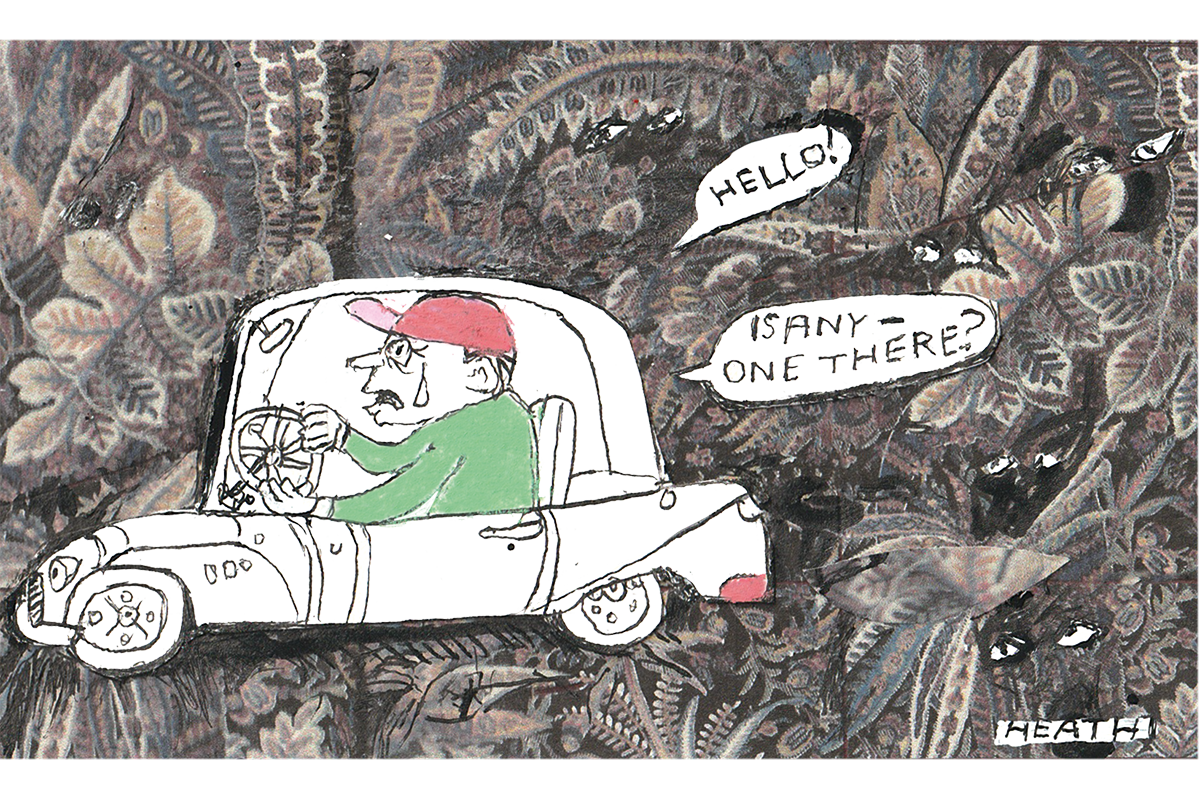

When my family farmed in West Kilimanjaro, in Tanzania, my father had a fine Boran bull called Larasha. He adored that bull, which he had bought from the great Boran rancher Miles Fletcher in Kenya. At that time, a troublesome lion was regularly killing cattle out in the bomas of the neighboring Maasai pastoralists. One night dad’s stockman was driving home in our old Series 3 Land Rover, which had no windscreen or top, when the headlights illuminated a male lion on the track. He slowed down, expecting the beast to move off, but instead it placed its front paws on the radiator and roared at him. The alarmed stockman accelerated forwards and the lion, with its growling mouth visible over the bonnet and its hind legs planted on the ground, pushed back. The Land Rover’s wheels churned in the dirt, the lion roared and the two were locked in a deadly scrum. Then suddenly, the creature leapt up on to the vehicle and bit right into the rubber of the spare tire fixed on the bonnet. A blast of punctured air shot up into the lion’s face with sudden force, its fanged cheeks and black mane riffling in the wind, so that it was thrown backwards off the vehicle, allowing the now terrified cattleman to race off into the darkness.

On inspection later, a large tooth was found embedded in the shredded spare tire. My father suspected this must be the lion that had been troubling the Maasai — and its injury during the encounter with the Land Rover now made it even more of a threat to livestock. Very soon afterwards, the beast barged its way into one of our cattle bomas, jumped on to the humped back of that fine bull Larasha. With one mighty swipe of his paw the lion broke the bull’s neck and immediately he set upon its carcass, tearing into its guts. The herdsmen, who had been snoring nearby, woke up and gave the alarm. With shouts and whoops, the cowboys tried to shoo off the lion, but only when a man appeared with a shotgun and began blasting away, did the bloodied predator withdraw.

In his younger days my father hunted a great deal, but when he married in his forties and settled down to ranch on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, he resolved never to shoot another living creature. Yet now, of course, he had to act. Alongside the Land Rover the family owned had a Datsun pickup with a closed cabin. The next evening, as night fell, he parked this vehicle in front of the half-devoured bull’s carcass, then took up position in the back of the pickup with his rifle and a torch. At the wheel of the Datsun he placed my mother, with instructions to switch on the headlights when he told her to do so. He would let her know by tugging on a string, which he passed through the window and tied to her little finger. On my mother’s lap lay a baby — me — blissfully sleeping, making not a sound.

The hours crept by and my mother, having almost held her breath in the tension for so long, began to doze. Suddenly she woke up with the gentle tugging of the string on her finger. In front of the car, she could hear sounds of gnawing and scrunching of bones. She flicked on the lights and there he was, the great lion, tearing at the bull Larasha’s flesh. Startled by the lights, he looked up, yellow-eyed, bloody-mouthed, freezing there for an instant before a single gunshot shattered the night. The lion collapsed on to the carcass and died.

I think I slept through the entire drama. The next morning some Maasai elders visited to celebrate the death of a creature that had slaughtered so many of their cattle. My father skinned the animal and cured the rawhide in a drum of cattle salt. Growing up, the hide was laid across the floor at home and I used to lie on it, urging dad to tell me the story again. After a beer, if he was in a good mood, he sometimes would.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply