George Mallory bookended the twentieth century history of Everest with his pioneering attempts in the 1920s to climb the mountain — and with the spectacular discovery, in 1999, of his body high up on the North Face, preserved by the ice for seventy-five years after he had failed to do so. His flip remark to a journalist that he was climbing Everest “because it was there” became mountaineering’s most celebrated quote, while masking other less noble reasons.

Mick Conefrey has become one of our finest gazetteers of the Himalaya, with successive books on K2, Kangchenjunga and later exploits on Everest. Now he turns his attention to a great conundrum of mountaineering history. Did Mallory reach the summit before dying — along with the moral question it prompts: should he have even tried, with imperfect oxygen equipment, given that he was putting not only his own life at risk but that of his much younger companion, Sandy Irvine, only twenty-two and fresh out of Oxford?

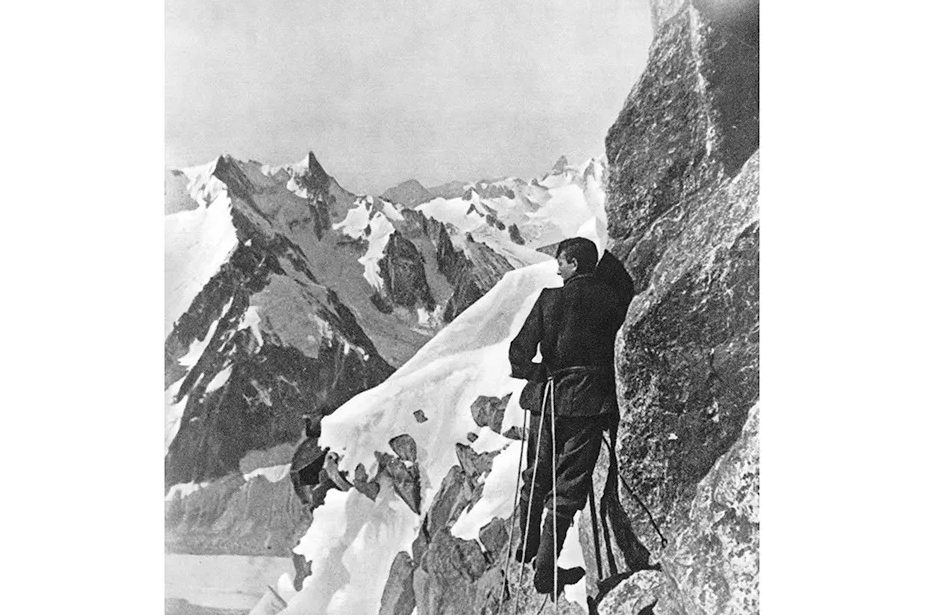

Mallory belonged to an older generation (he was thirty-seven, and had served in World War One) and was climbing with the recklessness of a man who knew this might be his last opportunity to have a go at the summit. Both he and Irvine were last seen on the Tibetan side of Everest — at that point, with Nepal closed, the only approach route — heading into the clouds from which they never re-emerged. Books like Mick Conefrey’s Fallen can have something of the appeal of a detective novel. At what point was the fatal mistake made that led to their deaths?

Mallory had premonitions about what might happen. Before leaving for that fatal attempt on Everest in 1924, he visited Kathleen, the widow of Captain Scott, and confessed to friends he was in two minds about whether he should leave his own wife and small children in Cambridge. In a way many will recognize, he never quite made the decision himself but let others make it for him. The Everest committee were determined that their finest climber would be part of the team, and Mallory’s wife Ruth did not want to be seen to dissuade him from going.

At the heart of it all, as with so many mountaineering disasters, was a clash of personalities. On the previous Everest expedition of 1922, Mallory’s fellow climber, George Finch, who was Australian, annoyed him with his sharp elbows and perceived chippy antipodean attitude. Finch had also managed to climb higher than Mallory using oxygen bottles, which the rest of the team thought was somehow cheating: “Only rotters would use oxygen.”

Now, it appears, Mallory had told the committee, as one of his deferring mechanisms, that he would not think of joining the new expedition if Finch was going; so they fired Finch to persuade Mallory, and he was left with little alternative but to prove he was a better climber on the day, whatever risks might be involved.

However, Mallory had a fatal flaw, well known to his companions. He was one of those people who are both absent-minded and clumsy with equipment. His leader on the previous expedition, Charles Bruce, had said that, left to his own devices, Mallory would forget his boots. What might be endearing on a stroll on the park — your laces are undone again — becomes a liability above 21,000 feet in the death zone of Everest. Mallory, unlike Finch, had never mastered the intricacies of using the large, awkward oxygen bottles without which Everest becomes even more daunting, particularly if on a pioneering route.

Had Mallory resolved his issues with the practical Finch, they would have made a formidable climbing partnership. Instead, he took the young Irvine, who had the great advantage in a climbing partner of doing exactly what he was told, however inexperienced.

Other writers, such as Wade Davis, have drawn the analogy with the fatalism of World War One in which so many of those early climbers had served. They took far more risks on Everest than would be taken today and often followed orders blindly. Finch was unpopular because he dared to question authority and perceived wisdoms; he designed the first duvet jacket for himself, an object of derision and then of envy when it became obvious how much warmer it was.

When Mallory’s body was found by an expedition which had gone to the North Face precisely for that purpose, his thin tweeds were all perfectly preserved — as was the nametape on the back of his shirt. Conefrey is particularly good on such granular detail. Irvine’s body has never been found, and he is perhaps the more tragic figure: the big, burly rower who had done little mountaineering, and whose boundless enthusiasm was sacrificed to the British need to claim the world’s highest mountain.

The mastermind of the expedition in London was Francis Younghusband — the same man who had shot unarmed Tibetans in the punitive 1903 expedition he led through the Himalaya to Lhasa, one of the least glorious of British colonial ventures. It was not enough to have proprietorially renamed the Tibetan Chomolungma as Everest; the summit was another place that needed conquering.

Irvine was the victim of a mindset that used the eagerness of youth as fodder for its own imperial ambition. The memorials to the missing of World War One could apply equally well to him; and, as the expedition was leaving, one of his surviving companions referred to Everest as “the finest cenotaph of the world.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.