“Why,” Thomas Pfau asks in the Hedgehog Review, “have death and dying been experienced as essentially incomprehensible” in the past 200 years? He continues:

Death is experienced as the total absence of meaning and, consequently, as something not to be understood but merely to be managed by drawing on medical ingenuity, pharmaceutical resources, and the (increasingly limited) forbearance of insurance companies. The recent loosening of centuries-old restrictions on physician-assisted suicide is but one feature of a multipronged approach that seeks to manage and expedite dying.

Writing in 1910, the German sociologist Georg Simmel may well have understood that he was fighting a rear-guard action when he warned against precisely this reductive conception of death as negation. As he noted, such a naturalistic account of death as something to be avoided, postponed, and denied ultimately ends up understanding “each of life’s steps…only as a temporal approximation of death.”

In Commentary, Joseph Epstein writes about the experience of mourning the death of a loved one:

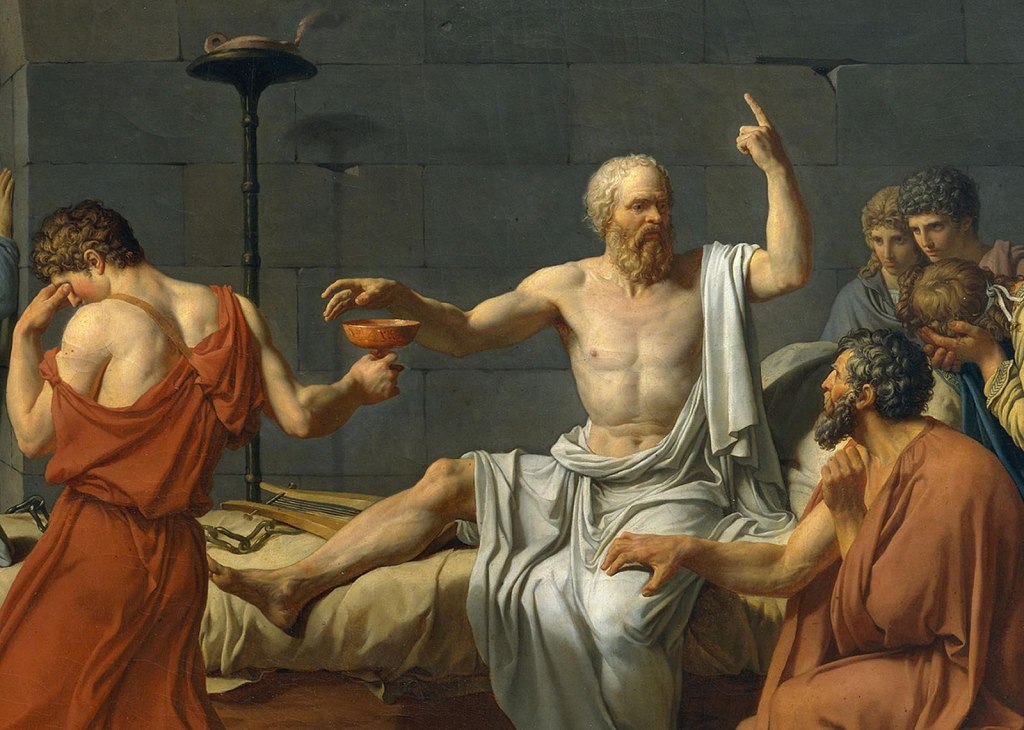

Socrates held that one of the key missions of philosophy was to ward off our fear of death. Upon his own death, by self-imposed hemlock, he claimed to be looking forward at long last to discovering whether there was an afterlife. Montaigne wrote an essay called “To Philosophize Is to Learn How to Die,” in which, as elsewhere in his essays, he argues that, far from putting death out of mind, we should keep it foremost in our minds, the knowledge of our inevitably forthcoming death goading us on the better to live our lives. But no one has told us how to deal with the deaths of those we love or found important to our own lives. Or at least no one has done so convincingly.

In other news

Despite being among the most entertaining and accessible of Romantic authors, Charles Lamb (1775–1834) has been out of fashion for many years. After his death, generations of Victorians and Edwardians continued to be charmed by his essays, letters and children’s books. But he exerted less lasting influence than more philosophical peers, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, and in the interwar period, changing tastes and Leavisite critical hostility contributed to Lamb being dropped from the popular Romantic canon. Lamb has always attracted admirers (notably in the ranks of the Charles Lamb Society) and numerous books on aspects of his life and work have been published. Yet, as Eric G Wilson observes, Dream-Child is the first full-scale biography in over a century. Covering the gamut of Lamb’s life and literary career, Wilson aims to demonstrate that Lamb “speaks to our age”, highlighting his enthusiasm for “the grit and speed and diversity of the urban” and his “fluid, collaborative vision of identity”.

The Library of America almost didn’t happen. David Skinner tells the story in Humanities: “The nonprofit publisher Library of America has released almost two hundred seventy volumes of classic American writing. Its black dust jackets with an image of the author and a simple red, white, and blue stripe running below the author’s name, rendered in a fountain-pen-like hand, help give the clothbound volumes a timeless feel, as if copies might have been found in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s dorm room or Henry James’s steamer trunk. But the series is nowhere near that old. It began publication in 1982. It did, however, take a long time to become a reality.”

The uninhabited river island that is both French and Spanish: “Border irregularities are found throughout Europe – and the world – but a 200m-long island that swaps countries biannually is unfathomably odd.”

Black kids should study Philip Larkin, Tomiwa Owolade writes: “The viewpoint of the curriculum decolonisers is based on the assumption that black students resonate most with poetry written by black poets. That is nonsense.”

Chris Vognar praises Jon Mooallem’s essays, which are more like “epic feature stories, deeply reported over a long period of time.”

The history of America’s most mocked paintings: “Long ridiculed, the Howard Chandler Christy artwork of the signing of the U.S. Constitution shows democracy at its most realistic.”

In my last column for Spectator World (more on that later), I write about some fall books I’m looking forward to reading.