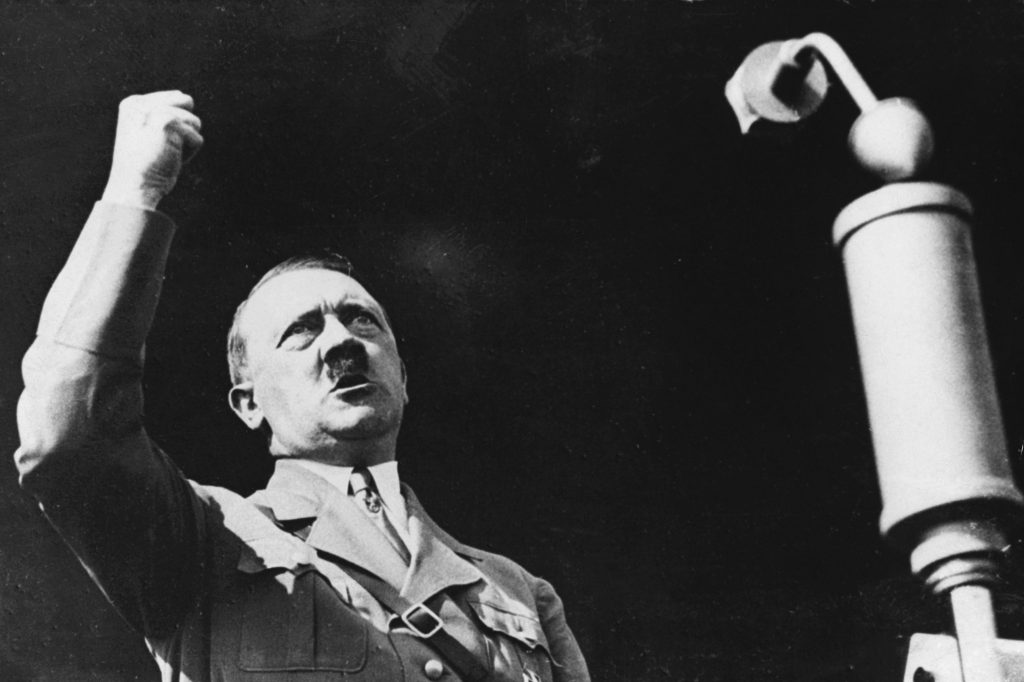

We care about Adolf Hitler’s penis, as a society. Quite a lot, it seems. A British documentary claims, finally, to have solved the mystery of the Nazi leader’s schwanz – was it big or was it small? – and to have proven, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the famous chant of “Hitler’s only got one ball,” a favorite among British soldiers, wasn’t just an idle insult.

The key evidence is genetic: a blood-stained piece of fabric from the Hitler bunker. The documentary filmmakers tested it against a sample from one of Hitler’s closest living relatives to make sure the blood was his. And it was. That meant his genome could be sequenced and then analyzed for genetic clues about his personality, health and, of course, his manhood.

A similar venture in 2014 failed when the disgraced historian David Irving sold filmmakers a strand of the Führer’s hair – only for it to turn out to be someone else’s. The documentary puts to bed some persistent myths about Hitler, not least of all the secret Jewish ancestry thing. Hitler was not secretly Jewish. But what about his penis? A missing nucleotide base suggests Hitler had Kallmann Syndrome, a condition that affects the onset and course of puberty and can lead to various forms of genital malformation, as well as lifelong low testosterone. Around10 percent of sufferers will have a micro-penis: a very small penis, typically less than 2.7 inches in length when erect. But none of this proves anything. It doesn’t prove Hitler had a micropenis or any other kind of physical anomaly, not even low testosterone. It just makes these things more probable.

As we might expect, the documentary relies more on innuendo and supposition than hard fact. There is, at least, a medical report from the early 1920s that says Hitler had an undescended right testicle. Otherwise that’s it. The report was only discovered in 2010, so it can’t have been the basis of the famous chant. The film asks why Hitler would have asked to be cremated. Was he trying to hide something? The answer, actually, is that he made the request late in the war, after he saw the mess Italian partisans made of his old friend Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci. He didn’t want to suffer the same fate. But surely something must have been really bugging Hitler to make him so power-mad? Surely he must have been compensating for something to want to invade Czechoslovakia and then Poland, and then France and then Norway and then, fatefully, the Soviet Union? No normal man with a normal penis would want to do that.

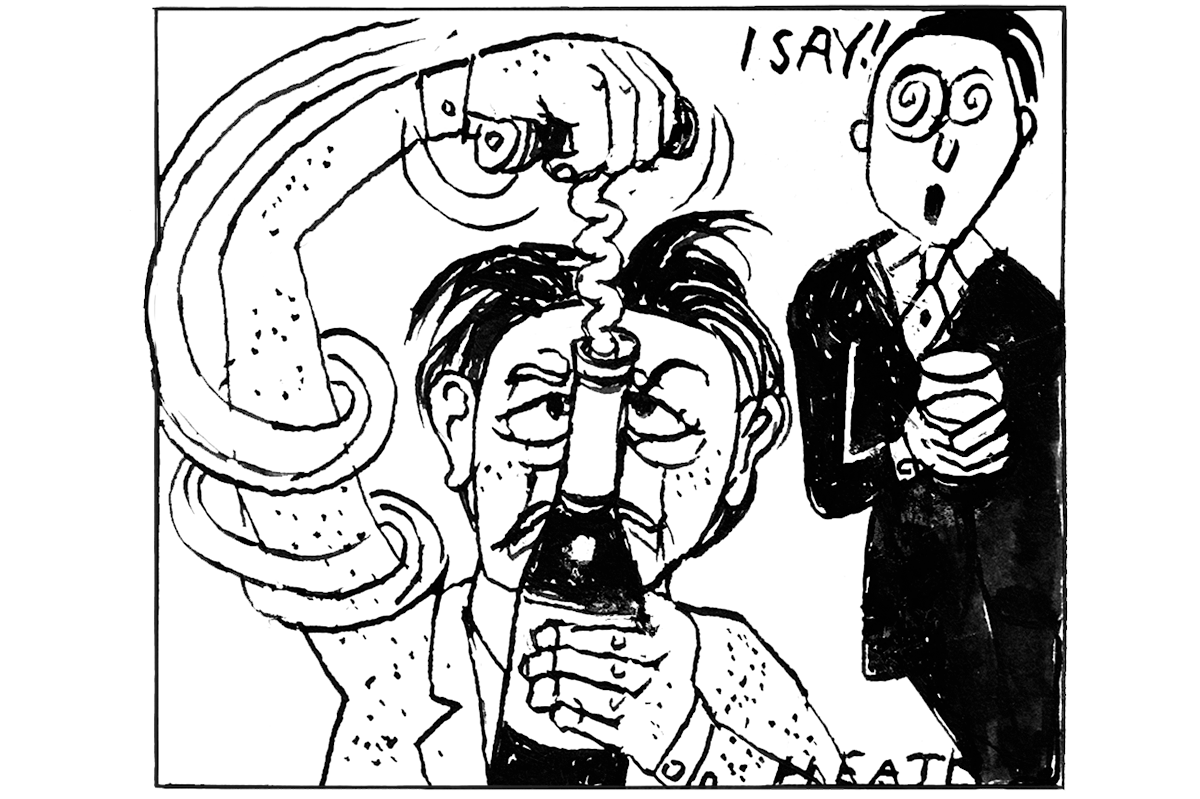

Here we reach the crux of the matter. I’m not about to launch a defense of Hitler and his virility. But I do think it’s worth asking, quite seriously, why we believe any of this matters. There is a “small penis theory of history,” and its target is always those who might once, before the advent of Leopold von Ranke, have been called “Great Men”: towering figures who, for good or ill, decided the fate of nations and whole epochs. This theory has a wide currency. You’ll hear it at middle-class dinner parties. You’ll read it in tabloid papers and “serious” books, too. Virtually every ruler, especially a ruler of a more dictatorial bent, is accused at some point of having a small penis. In our own time, Vladimir Putin has been; and, of course, Donald Trump, including by former porn star Stormy Daniels.

Perhaps the most insidious variant of this tendency is something I call the gay interpretation of history. Rather like the Whig view of history, which sees everywhere and at all times a move towards the sunny uplands of “progress,” this degraded vision sees everywhere and at all times a move out of the closet into open homosexuality.

Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great, Achilles and Patroclus, the Spartans at Thermopylae, cowboys, pirates, soldiers, martial artists – any male figure from history is liable to be branded a repressed homosexual.

I was on the receiving end of such claims myself when I appeared in the 2022 Tucker Carlson documentary The End of Men, which was about plummeting testosterone levels and some of the things young men are doing to reclaim their masculinity. Those things included lifting weights, cleaning up their diets, doing martial arts, shooting guns and just spending time with other like-minded young men. The trailer for the documentary, which featured a montage of these activities, was greeted with howls of derision in the media. Talking heads and celebrities, everyone from Stephen Colbert and Cenk Uygur to George Takei, announced virtually in unison that The End of Men was a barely concealed gay Nazi fever-dream.

In his celebrated book The Four Loves, published in 1960, C.S. Lewis offered a withering rebuttal to the claim male friendship harbors a secret – or not-so-secret – sexual core. “Those who cannot conceive of Friendship as a substantive love but only as a disguise or elaboration of Eros betray the fact they have never had a friend,” he said.

It’s easy to blame Freud, the man who did more than anyone else, perhaps, to place sexuality at the center of our understanding of, well, everything. Yet, as much as I don’t like the Viennese witch-doctor, I’m not sure that’s right. There’s a reductive tendency in western thought that stretches back longer than the early 20th century.

We can say, though, with some certainty what the effects are. The reaction to The End of Men is a fine illustration: instead of empowering young men to improve their lives, society tells them to distrust their instincts and desires, to retreat from friendship and ambition and, for heaven’s sake, not to make a noise. “We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful,” said Lewis; we make “men without chests.” Lewis meant that metaphorically, but it’s also true in the most literal sense. Men possess a psychological and emotional depth and a range of needs that can’t be reduced to the heat between their legs. The sooner we appreciate that, the sooner we’ll understand the best – and worst – of what men have to offer. Until then, our conception of men will remain small, shriveled and not much use for anything.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 8, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply