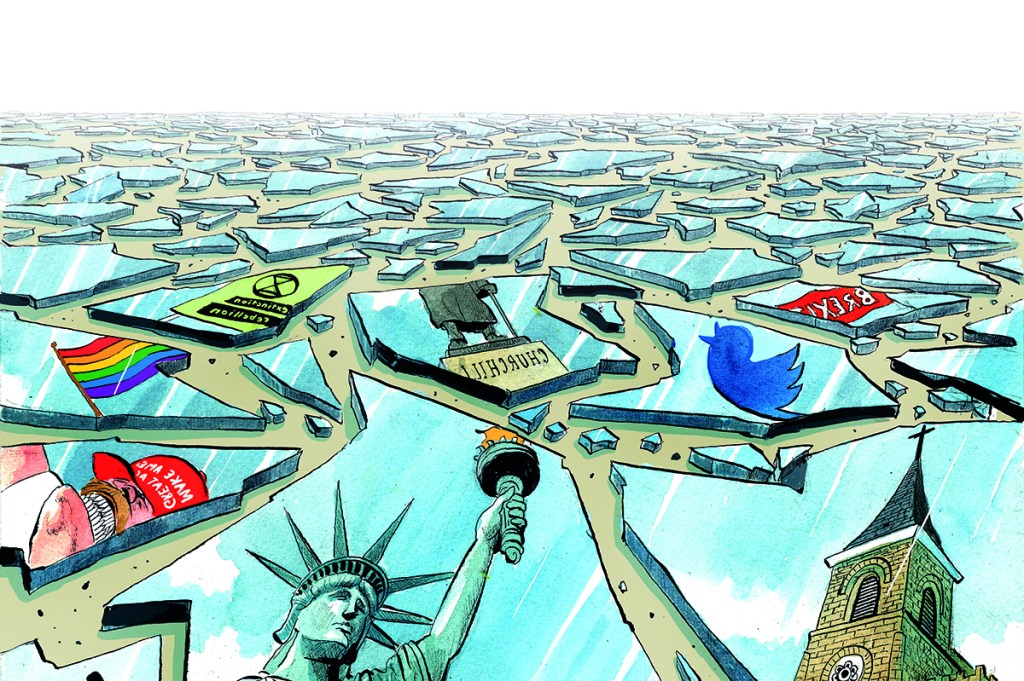

Low wages are bad for everyone in the United States — not just for the working poor. Every major social crisis Americans face today — falling fertility, the loneliness epidemic, bitter conflicts over racial and gender identity, and growing partisan polarization in politics — is worsened if not caused by the proliferation of low wage jobs caused by the collapse of worker power.

For centuries, children in the English-speaking countries have learned a proverb that has equivalents in other European languages (“want of” in this context means “lack of”):

For want of a nail, the shoe was lost. For want of a shoe, the horse was lost. For want of a horse, the rider was lost. For want of a rider, the battle was lost. For want of a battle, the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

Here is how a similar cascade effect works in the case of worker power. The diminished ability of workers to bargain collectively or alone allows employers to pay low wages to millions of Americans. Low wages and insecure jobs also contribute to many of the pathologies of the working poor, including disconnection from the workforce, lack of friends and social life, drug addiction, and “deaths of despair.”

For want of good wages America as a middle class republic is in danger of being lost

Fear of being trapped in low-wage occupations like retail, fast food, janitorial services, and low-end nursing cares drives people to try to get jobs by getting credentials, in the form of university degrees or occupational licenses. Taking part in the increasingly expensive credential arms race, in turn, leads many Americans to delay, and sometimes forgo, marriage, family formation, and childbearing, leading to fertility rates far below the levels needed for maintenance of the US population without high and economically harmful rates of unskilled immigration. Identity politics, which would exist anyway in a diverse society of different races, ethnic groups and religions, is worsened by its weaponization in the struggles of too many college-educated Americans competing for too few well-paying positions. Last but not least, the collapse of private-sector organized labor as a major political force has produced an overall decline in the political influence of working-class Americans of all races and regions, replacing the transactional politics of the New Deal era with bitter ideological struggles among factions of the college-educated, affluent overclass.

Thanks to these cascade effects of dwindling worker power, for want of good wages, America as a middle class republic is in danger of being lost.

***

Let’s begin with the demographic crisis. The marital and reproductive behavior of various classes in different civilized societies has always been influenced by the requirements of social status and property ownership.

In the twenty-first-century United States, as in most other advanced industrial nations, most people are wage or salary earners. The most important form of property is not a farm or a business or a house but a credential that gives the wage earner access to a stream of income — in most cases a stream of income from an employer, but in some cases income directly from customers or clients paying for licensed professional or technical services.

Whether in the form of college degrees or occupational licenses, credentials are usually time-consuming as well as expensive to obtain. Access to the best jobs in the United States increasingly requires not only a four-year college degree but also a graduate or professional degree of some kind, like an MA, an MBA, a law degree, or a PhD. The master’s degree is the new BA. Thanks to credential inflation, the PhD may soon be the new high school diploma.

The greater the number of degrees that people obtain, the more years they must spend in higher education. This explains why American workers with graduate and professional degrees tend to marry and form families later than those whose educations end with high school or a bachelor’s degree.

In return for postponing marriage and family life, successful professionals and managers with advanced degrees win the competition for access to cartelized professions like those of doctors and lawyers or full-time employment by medium to large firms that informally collaborate with their peers in illegal but tolerated wage-fixing “salary band” schemes. Those who do not go to college, or attend college but drop out at some point, usually must settle for inferior jobs and can never achieve the economic stability and middle-class lifestyle of which they dream.

Credentialism contributes to the “diploma divide” in marriage in the twenty-first-century United States. The most educated Americans are most likely to be married and most likely to stay married. Less educated Americans are more likely to never be married or, if they are married, to be divorced. Both working-class and college-educated Americans tend to live with their partners before marriage, but cohabitation among working-class couples is less likely to lead to formal marriage and more likely to break down in its absence.

To be sure, calling this the “diploma divide” is misleading. The main factor is the difference between good and bad jobs, not between degrees, which are mere tickets to good jobs. The marital diploma divide is about money, not about scholarship. Financial stress is a major cause of disruption in relationships and divorce. College-educated couples are more likely to stay together because they are more financially secure than working-class couples.

At the same time that there is a growing class and credential divide in marriage, birthrates are dropping below the numbers needed to replace the US population.

Advocates of the theory of “the second demographic transition” sometimes attribute the collapse in the total fertility rate to the voluntary choice of parents to limit the number of children they have. The evidence suggests otherwise. The chief reason for falling birthrates in the United States is delayed marriage and non-marriage, not a preference for fewer children. While few contemporary couples want the large families of premodern agrarian societies, polls consistently show that most American parents wish they had more children than they end up having. The American fertility rate of 1.77 is far below the average number of children that American women, native and immigrant alike, desire: 2.7. When asked why, parents who wish they had more children often blame inadequate incomes or the need to postpone marriage and childbearing until a level of economic security or professional rank has been achieved.

Delayed marriage is the main reason that couples do not have as many children as they want, given the biological limits to female fertility. And the main reason for delayed marriage and postponed childbirth is credentialism — the need to amass one or more university diplomas, in order to have access to a well-paying, stable job as a precondition for marriage and family formation.

One older woman of my acquaintance complained, ‘I wanted grandchildren and all I get are diplomas’

In most industrial countries, birthrates have fallen below the number needed to replace the population. This has occurred both in countries with generous welfare states and high levels of unionization and in those without; social democratic Finland has experienced one of the steepest declines. The key factors in otherwise different countries appear to be delays in childbearing by women seeking educational credentials and the difficulties caused for childcare by participation of mothers in the workforce. A 2019 study of women in the UK, for example, found that “increasing attendance in higher education has a largely direct effect on early childbearing up to twenty-five years, resulting in a substantial increase in childlessness.” More diplomas for fewer children may be a bad trade-off for many, given the reality of degree inflation, which results in increasing time and money wasted on higher education to obtain credentials that are not really necessary for many jobs.

Credentialism causes far fewer Americans to be born than might have been in an alternate world in which obtaining stable, well-paid jobs did not so often require people to spend their twenties and sometimes their thirties in school. As one older woman of my acquaintance complained, “I wanted grandchildren and all I get are diplomas.”

***

Credential inflation plays a part in what might be called the American social crisis as well. For those who fail to climb the credential ladder out of the pulverized and powerless American working class, the American dream can turn into the American nightmare.

In the 2010s, the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton shocked the world by documenting an epidemic of “deaths of despair” caused by suicide, alcohol, opioid addiction, and other factors among working-class white Americans. Deaths of despair were concentrated in deindustrialized regions of the Midwest and South from which good-paying union jobs in factories had disappeared as a result of Chinese import competition and offshoring by US companies to low-wage workforces in China, Mexico and elsewhere.

More than a loss of income was involved. For men and women in midlife to go from stable, decently paying jobs to insecure work or dependence on welfare is humiliating. At the same time, the young are demoralized by growing up in communities with boarded-up factories and stores and shrinking populations, where more money is sometimes to be made in petty or organized crime or reliance on public assistance than in regular jobs. Many of these same social pathologies earlier afflicted urban African Americans and others when factories had abandoned Northeastern and Midwestern urban areas, sending entire neighborhoods and metro areas into decline. The crack epidemic in blighted urban America in the late twentieth century foreshadowed the opioid epidemic that swept rural and small-town America in the twenty-first. The patronizing phrase “left behind” implied that there were plenty of good jobs waiting, if only the victims of sectoral or regional economic change would move or upgrade their educational credentials. But as we have seen in earlier chapters, great numbers of good jobs with good wages and benefits to replace the unionized manufacturing and manufacturing-related jobs that have been eliminated by offshoring and de-unionization are not being created in the United States.

Another intangible cost that contributes to the social crisis of the downwardly mobile American working class of all races is what the French social theorist Émile Durkheim called “anomie” — normlessness or disorientation or alienation. Here again the destruction of private trade unions by American businesses and their allies in government has had ripple effects throughout society. Many unions had been the center of the social lives of their members. The collapse of unions, along with the decline of church attendance, is creating greater disconnection and isolation among members of the American working class of all races than existed a few generations ago.

What was once the rich associational life of much of the American working class in all too many places has become a social desert

Civic associations have failed to fill the gap. The local mass-membership organizations that flourished in the middle of the twentieth century, like the Shriners and Jaycees, have been displaced by a new kind of nonprofit organization. The professional staffs of these “astroturf” orgs tend to view local working-class populations rather as nineteenth-century European and American missionaries viewed non-Western “natives” — as primitives in need of rescue from barbarism by enlightened saviors, not as neighbors and peers whose major problem is a lack of economic and political power.

The greater rates of non-marriage and divorce among working-class Americans also contribute to anomie. Parents often meet neighbors and colleagues through the shared activities of their children. The link to a wider community that the family provides is not available to men and women who are un-marriageable because of their low wages and inadequate credentials, and may not be available either to married partners or members of a cohabitating couple after a breakup. What was once the rich associational life of much of the American working class, centered on unions, churches, clubs, and local political parties and supplemented by friendship with neighbors, in all too many places has become a social desert.

Between 1990 and 2021, the number of American women who reported that they had six or more close friends fell from 41 percent to 24 percent, with 10 percent saying they had no close friends at all. The decline of friendship among American men has been even more pronounced, falling from 55 percent with at least six close friends in 1990 to 27 percent, while the number of men reporting no close friends has risen in the last thirty years from 3 percent to 15 percent. Friendship, like family formation, is withering away in the United States.

***

To the demographic crisis and the social crisis, we can add the American identity crisis. While the social crisis tends to affect working-class Americans who never took part in, or dropped out of, the credential arms race, the identity crisis is driven by college-educated Americans who fear that not enough good jobs are available for those with their qualifications.

What has been called “the Great Awokening” of the 2010s and 2020s has many of the features of the Protestant revivals of the American past. Instead of confessing their sins, woke Americans confess their racism, sexism, and homophobia, using a curiously stilted, liturgical language.

Baptism into the new faith of woke progressivism brings with it a new vocabulary — “birthing people” for mothers — and a catechism — “some men can get pregnant,” and “color blindness is a form of racism.” As with religious conversions, the born-again woke may adopt new identities, sometimes racial or ethnic but more frequently related to gender, like “nonbinary.”

Paradoxically, although denouncing white America is one of the rituals of performative woke leftism, the woke left is much whiter than the US population in general. Studies have shown that affluent, college-educated whites are more likely to adopt woke attitudes and language than working-class black and Hispanic Americans, who tend to be moderate cultural conservatives. Using a phrase coined by the author Peter Turchin, many have attributed wokeness to “the overproduction of elites” — and in particular to the overproduction of college graduates. Turchin’s cyclic theory of history can be disputed, but given the social base of the Great Awokening among white college graduates, the concept is plausible when more narrowly applied.

One applicant got into Stanford in 2017 by writing an application letter that consisted of nothing more than one hundred repetitions of the slogan ‘#BlackLivesMatter’

Thanks to the credential arms race, far more young Americans apply to colleges and universities today than in earlier generations. Increasingly, college applicants are distinguishing themselves from the competition in application letters by means of their “identity credentials,” emphasizing their membership in this or that racial or sexual minority or weaving into the letter phrases from the ritualized “social justice” lexicon that might appeal to the overwhelmingly progressive university admissions committees. One applicant got into Stanford in 2017 by writing an application letter that consisted of nothing more than one hundred repetitions of the slogan “#BlackLivesMatter.”

The competition among graduates is just as fierce as among applicants. According to the Federal Reserve in 2020, 41 percent of recent college graduates work in occupations that do not require a college diploma. A 2021 study by Burning Glass found that two thirds of the four in ten college graduates who are underemployed in their first job will still be underemployed five years later, and of those, three quarters will be working in non-college jobs after a decade.

One strategy adopted by elite institutions to absorb surplus graduates, particularly those with degrees of limited market value in gender studies or minority studies, has been to multiply the number of well-paid make-work jobs related to “diversity, equity, and inclusion” — college campus DEI bureaucracies, corporate HR offices, consultancies that specialize in “diversity training” for firms and government agencies and nonprofits. Illegal but government-tolerated quota systems ensure that many of these make-work jobs will go to workers whose race, sex or gender self-identification gives them an edge over their white or male or heterosexual competitors.

In other career tracks in highly prestigious professions and companies, ideology rather than identity can be deployed for self-advancement. Office Machiavels can weaponize “wokeness” to bring down supervisors or other colleagues standing in the way of their career ambitions by “calling them out” for “microaggressions” and pressuring risk-averse management to fire those who are denounced, thereby opening up new organizational career pathways for the denouncers.

In short, one unanticipated but major social result of the credential arms race has been a spin-off competition: the identity credential arms race.

***

Like other pathologies of contemporary American society, today’s partisan polarization is influenced indirectly by the decline of worker power.

Mid-twentieth-century America not only had the first (and last) mass middle class in American history but also was built on mass politics. The political system was shaped by the influence of mass-membership organizations: trade unions, the once-powerful farmers’ organizations, well-attended churches, and fraternal and civic organizations. The Democratic and Republican parties themselves were national federations of state and local parties, in which great numbers of Americans took part in some way.

The result was what the journalist John Chamberlain in his 1940 book The American Stakes described as “the broker state.” Politicians and government administrators brokering deals among the organized groups of organized blocs naturally tended to produce a transactional politics with plenty of room for compromise among the big players — business, labor, the farm lobby, urban political machines.

That world has vanished. The destruction of private-sector unions by American business and government has eliminated the major institution that empowered working people, apart from their participation as voters in the political system. Half a century ago, labor leaders like Walter Reuther and George Meany were household names, powerful leaders who negotiated with presidents and congressional leaders as well as corporate executives. Today, many union members themselves would be hard-pressed to name any national union officials. Public-sector unions continue to influence the Democratic Party, but the decline of private-sector unions has resulted in the near-monopoly of lobbying about private sector economic issues by business interests, influencing Democrats and Republicans alike.

The parties themselves have changed from mass-membership federations into brands bankrolled by billionaires

Meanwhile, the parties themselves have changed from mass-membership federations into mere brands bankrolled by billionaires and corporations and responsive chiefly to members of the college-educated overclass. The decision of both national parties in the 1970s to select candidates in open-party primary elections or caucuses, rather than in conventions dominated by career politicians, was intended to make American politics more democratic. Instead, the primary system has made American politics more oligarchic.

For decades primary voters as a share of eligible voters has fluctuated between 10 and 30 percent, compared to around 40 percent in midterm general elections and around 60 percent turnout in general elections in presidential election years. Moreover, the small number of voters who take part in party primaries are not typical of their own parties. They are better educated, more affluent, and more ideological than most Democrats and Republicans. A study in 2018 found that 62 percent of Democratic primary voters and 58 percent of Republican primary voters had bachelor’s degrees or more, compared with only about a third of the American public. At a time when the average household income was $60,309, more than half of the primary voters in each party came from households making more than $75,000 a year. Affluent Democrats and affluent Republicans alike tend to be motivated by “post-material values” and passionate about polarizing social issues like abortion or gun control, unlike America’s multiracial working-class majority, whose chief concerns according to pollsters are quotidian issues like the economy, health care, and safety from crime. The well-educated and well-off Democrats who are overrepresented in Democratic primaries drag the party to the left of most Democrats on social issues. At the same time, the Republican Party is dragged to the right of median Republican voters on social issues, not by the ignorant working-class yahoos demonized by snobbish progressives, but by petit bourgeois and professional-class Republicans motivated by culture war zeal.

Along with upscale, educated, hyper-ideological primary voters, the selectorate of each party includes affluent party donors. As Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page showed in a celebrated study in 2014, elected officials of both parties tend to side with the donors against the voters in the party, on issues where the two groups have opposing views. As a whole, the American donor class forms a relatively homogeneous bipartisan establishment whose members have more in common with each other than with most Democrats or Republicans. The oligarchs of the American campaign donor class tend to be more liberal than the general public on social issues, as well as more free market oriented and more in favor of free trade, mass immigration, and American military interventions abroad. Members of the American donor class, from the elites of Silicon Valley and Hollywood who support Democrats to the fossil fuel and agribusiness executives who are more likely to fund Republicans, along with Wall Street donors who can be found on both sides, tend to share a hostility to organized labor in their own private sector industries.

All of this explains the otherwise puzzling gap between the policy preferences of Democratic and Republican voters and the actions of their elected representatives. Elected officials in both national parties respond chiefly to their elite selectorates — affluent primary or caucus voters and donors — not to the party electorates made up of ordinary, mostly working-class voters of diverse backgrounds.

Forty-seven percent of Republican voters approve of labor unions, but almost all Republican elected officials are hostile to organized labor, thanks to the party’s overwhelmingly libertarian and corporate donors and its well-off primary voters. Majorities of black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans, who vote disproportionately for Democrats, have long wanted police funding to stay the same or increase. But many affluent white progressives and elite nonwhite activists have led many cities under Democratic rule to slash funding for the police, tolerate high levels of property theft, and eliminate bail requirements, during a crime wave.

Majorities of African Americans (62 percent), Hispanic Americans (65 percent) and Asian Americans (58 percent), who vote disproportionately for Democrats, as well as non-Hispanic white Americans (78 percent), who are mostly Republican, agree that “colleges should not consider race in admissions,” according to the Pew Research Center in 2019. Meanwhile, major universities in the United States, in which elite Democrats make up almost all of the professors and administrators, in the name of “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” have adopted de facto race-based quota systems for admissions and faculty hires and even classroom curricula. The pressure for rigid race and gender quotas in all areas of American society is not coming from below.

Even street-fighting zealots of the far left, like antifa, and the far right, like the rioters who stormed the US Capitol, are disproportionately members of the American elite

Even the street-fighting zealots of the far left, like antifa, and the far right, like the rioters who stormed the US Capitol on January 6, are disproportionately members of the American elite, not the working class. Investing in “black bloc” anarchist outfits is expensive, and so is traveling from city to city to take part in leftist protests and sometimes to engage in violent clashes or vandalism. Likewise, the militant supporters of President Trump who could afford plane tickets and hotel rooms in Washington, DC, as the price of taking part in the pro-Trump “Stop the Steal” protest on January 6, were not poor.

As the influence of the organized working class diminishes, and as politics becomes a game for college-credentialed professional elites and the wealthy, representative democracy becomes an arena for the rule-or-ruin feuds of ambitious oligarchs and their retainers.

All four crises — the demographic crisis, the social crisis, the identity crisis, and the political crisis of partisan polarization — might exist in some form without the collapse of American worker power and the resulting low wages and credential arms race. But there is little doubt that higher wages at the bottom, and a restoration of both individual and collective worker bargaining power, would reduce many of the tensions in American society.

This excerpt is adapted from Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages is Destroying America by Michael Lind with permission from Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC copyright © 2023 by Michael Lind