There are many in Donald Trump’s inner circle who have tried to read his mind these past four years, together with a class of journalists who, on a daily basis, have catalogued his whims and outrages. But perhaps my attention to the former president, after writing three books about him, is unique. I now regard him as my own character, with an ever-so-fine line between what he actually does and what, in moments of inspiration, I imagine him doing. I am not always able to tell the difference in the Twitter of my dreams.

We have a cottage in Amagansett, the most un-Hamptons Hamptons town (making it, in fashion’s dialectic, the most Hamptons town), that was bought with the proceeds from my books about Trump. Among its hoped-for benefits is to help me forget about him. Of course the main subject in the Hamptons is still Donald Trump. As a defeated politician, he may yet be, like almost all modern public figures, a streaking comet, merely brighter than all others, but gradually burning out. But, in a much different metaphor, and occupying a much different status than mere former president, he could be an ongoing fact and condition of modern life, like Google, or COVID.

I am a de rigueur guest at Hamptons dinner tables. Perhaps I am like a war correspondent returning from the front in pre-television days. At the appointed moment of an evening, all eyes turn to me for an update on the fraught situation. Although more airtime, column inches and social media angst have been devoted to Trump in a concentrated period of time than perhaps to anyone else in history, the hunger for information about him is never sated. Mine is not the only book about the former president topping the summer bestseller lists. On Hamptons lawns, with the mist rising in the early evenings, his name is not even used. It is merely ‘He’. ‘Will he run again?’ ‘Is he really crazy?’ ‘But is he clinically crazy?’ ‘Is he going to jail?’ ‘Why does Melania stay with him?’ ‘Will he push Ivanka to run for president?’ No matter how much has been said about him, he remains an unexplained phenomenon. The fact that so much press rancor has failed to destroy him, or even make much of a dent in his iron support, suggests parallel worlds — we are all pressed to the glass. Nobody is an insider.

The frustration with this perceptual gap, this inability, after four years and a deluge of information, to unravel the mystery of his existence, got the better of me one recent morning. A mobile video truck arrived in front of our Amagansett house and I hopped in to do CNN’s Sunday morning media show, Reliable Sources. The show is hosted by a young man named Brian Stelter who has made himself quite a reputation as a kind of clergyman of journalism. His is a world of good and evil, black and white, righteousness or blasphemy. Such a religious view has, it seems to me, only increased the power of Donald Trump as it cements the iron curtain of the cultural divide. On air, I called the host out for his sanctimony. This became a viral moment with social media cheering my mild riposte. A surmise: there is a deep awareness of the limitations of modern journalism, a discontent with the humorlessness of it all, and an anger at the moral superiority which, among other things, has got in the way of telling a mind-blowing tale.

The Hamptons was once most famous for the writers and artists who quit the city to come out here. Now the eastern end of Long Island is most famous for its billionaires. It occurs to me that the disappearance of working writers in the Hamptons mirrors the absence of writers in US public life. This has left the most confounding story of our time, with a character as beguiling to many as he is monstrous to others, to political reporters specializing in policy, government procedures, and the means and ends of political agendas. The mindset of the official media has arguably prevented it from being able to enter and depict Donald Trump’s spectacularly insane world. Hence, the most transparent man on Earth — a man who seeks nothing more than to be on permanent public display — remains inscrutable.

Anyway, I do believe I have done my bit. It is time for me to retire my character, or have him retire. Of course, that is an event as unimaginable as all else that has been unimaginable about him. There is, alas, no life for Trump other than his constant, do-absolutely-anything bid for universal attention.

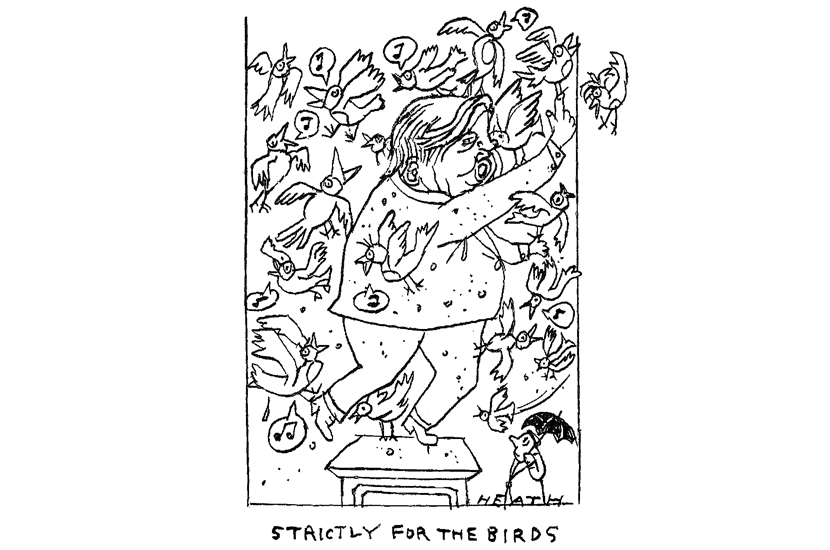

Birds have apparently become a distraction for many people during the pandemic. In our house we are spending hundreds of dollars a week on birdseed. This has got us a miraculous aviary of red-winged blackbirds, goldfinches, catbirds, woodpeckers, hummingbirds, titmice, chickadees, crows, cardinals, blue jays, robins, sparrows galore, and, one day, a great hawk swooping through, helping me take my mind off not just the Delta variant but, too, the seemingly permanent state of Donald Trump. No more, please. Let me be finished.

As I write, my old friend Andrew Cuomo has come tumbling down for, among other sins, according to one accuser, ‘micro-flirtations’. I cannot help but reflect that in a world where all politics is to the death, Donald Trump may be the one figure to have unlocked the winning formula: to transcend the details and the shame and glory in all attention of any kind whenever and wherever. That is the secret of eternal political life.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.