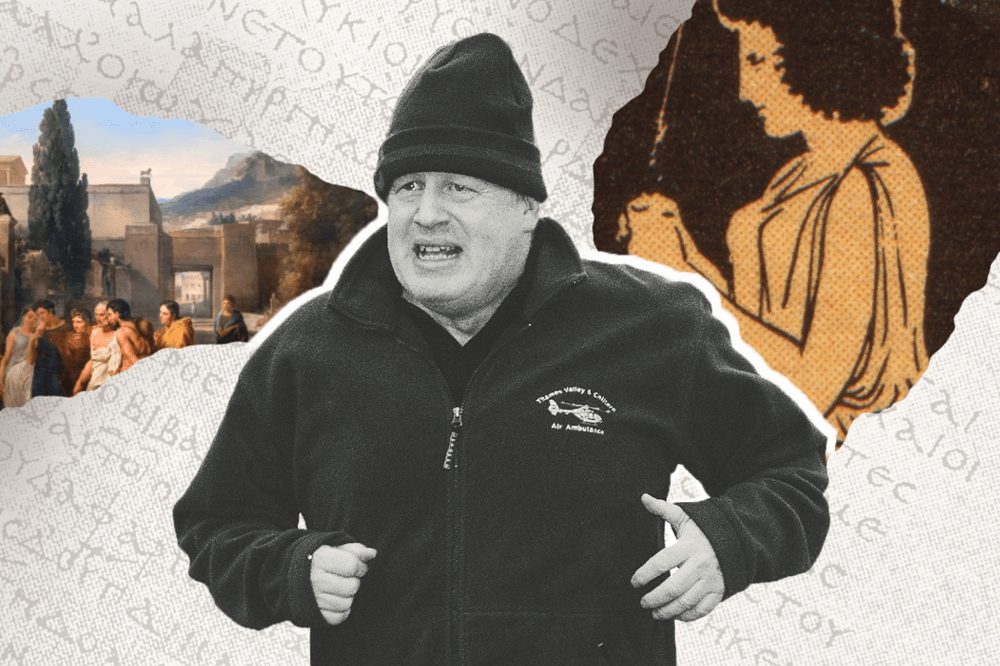

One of the joys of a recent career change is taking a slightly longer run in the mornings. I get up in the dark and hammer my way round the park with the Protforce detectives strolling behind (and breaking into a theatrical jog when I turn round). There is nothing more beautiful than watching the sun come up over a frosty London, and seeing the light begin to gleam on the tops of those high-rises — tastefully located — that I helped to greenlight, with Eddie Lister and Simon Milton, when we were running City Hall. As I trundle along, I brood on my next moves. I think I have cracked it.

One way to take your mind off the rigors of athletic exertion is to recite poetry. I now have a pretty stonking repertoire. In thirty-five minutes I can do the first 100 lines of the Iliad, the first 100 lines of the Aeneid, the first canto of the Divine Comedy and the whole of Lycidas. I am pretty much word-perfect, though I might hesitate over the names of all those flowers towards the end of Lycidas and I am not sure a real Italian speaker would enjoy my version of Dante. But I have at least been able to meditate on these amazing works of art.

The openings of the first two, the Iliad and its majestic Roman successor, are really what you call suppliant dramas. One character turns to another and implores them to do something. I like to act them out in different voices — much to the puzzlement of people overtaking me. I love Juno begging Aeolus to destroy the Trojan ships, and offering him sex with her most beautiful nymph. But my favorite is the old priest Chryses, begging Apollo to punish the Greeks for dishonoring him and for refusing to accept the ransom he has offered for his daughter — otherwise doomed to occupy the bed of Agamemnon. He ends with that fantastic line about the twin silver rains: “May the Greeks pay for my tears by your arrows.” He prays to Apollo in all sorts of aspects. He calls him god of the silver bow, the ruler of Chryse and Killa and Tenedos. He then uses a title that has divided scholars for years.

He calls him Smintheus. What is Smintheus? I want to offer a new conjecture, or a new justification for the old translation that has fallen out of fashion. I was going to try the Journal of Hellenic Studies, but my old friend Armand D’Angour (one of the true geniuses of our time) gently suggested that it should go to you Spectator readers. You have all read Matt Hancock’s diaries. You know about the conflict that has divided Britain for the past three years. How should we deal with a terrifying new plague? In Iliad 1, the disease is ravaging the Greek army. The pyres are burning round the clock. Day after day it goes on, until Achilles can take it no more. He wants a proper scientific explanation, and he wants the Greeks to take radical action to stop the infection — setting sail and abandoning the Trojan War. Agamemnon disagrees. He rages at Achilles. He rages at Calchas the prophet (the Homeric equivalent of SAGE). He rages with all the fury of those stout-hearted people who thought the government was wrong to impose lockdowns. Yes, folks, western literature begins with a political feud about how to deal with a new and frightening disease — but what sort of disease?

We are told first that it is a disease that strikes from afar, like the silver arrows of Apollo, and we know that it can be passed invisibly through the air. Homer also tells us something specific about its origins. When Apollo shoots those arrows at the Greek camp, he hits first the mules and the darting dogs, and it is only later that the sickness species-jumps to human beings. In other words, it is a zoonotic plague. It began in animals, and that is surely why Chryses prays to Apollo as Smintheus, and why the old translation of Smintheus as “mouse-god” may well be right; because it was the mice that gave it to the mules and the dogs and then to humanity; just as winged mice — the bats of Wuhan — are believed, sadly, to have incubated so many coronaviruses. That was the process that the old priest imagined in his prayer. When he called on Apollo’s arrows, and he invoked the mouse-god, he was calling for something truly horrible to happen. It did. Agamemnon raged and swore. But he knew he was beat. The suffering was too great. He couldn’t ignore the soothsayer. He gave the old priest back his daughter, and punished Achilles for being right — with tragic consequences that enthrall us for the next 15,600 hexameters.

So, who knows, the first 100 lines of the Iliad may contain the first description of something like Covid as it sweeps through a human population; and the political row. Never mind doing podcasts or TV. I propose to fill this unexpected hiatus in my career with vast lucrative theatrical renditions of these great texts, in ascending chronological order. It’s going to be called “A Totally Epic Performance.” I expect you will laugh and say that no one will come. I say, who cares. You read it here first.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.