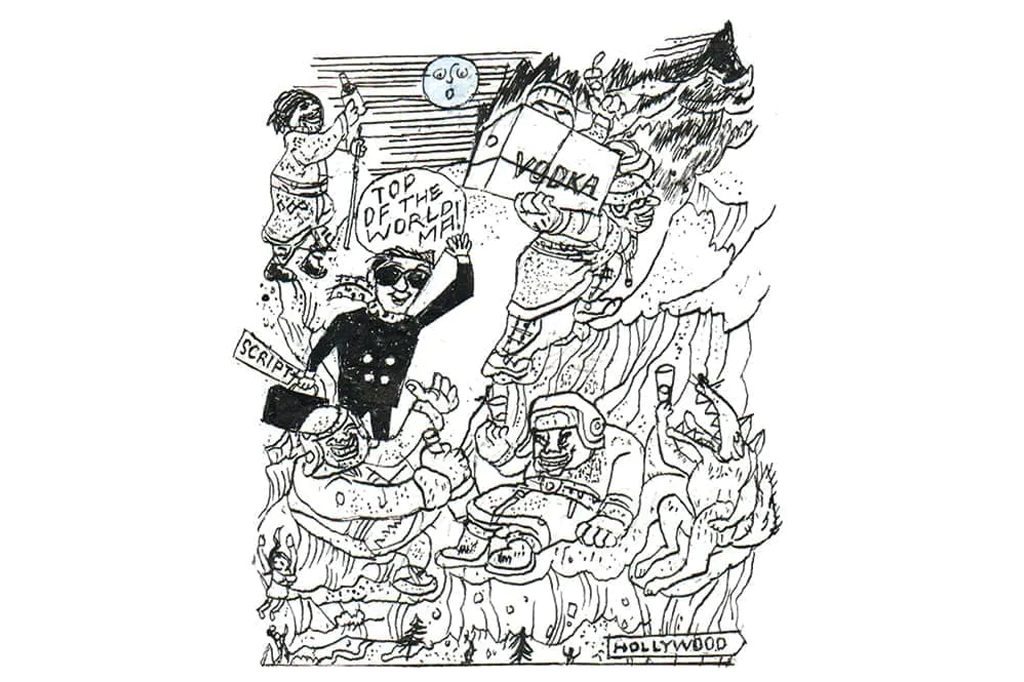

The first time I went to Mongolia was in 2014, when I traveled across the country with the actress Michelle Rodriguez and a group of her friends, courtesy of the Mongolian-American conservationist Jalsa Urubshurow. Driving out of Ulaanbaatar at dawn, we stopped at a market on the outskirts of the city to buy caviar, blinis and crates of Chinggis vodka for the twelve-hour drive. Because I was not a follower of the Fast & Furious franchise, I had little idea who Michelle was, but every vendor in that tiny market knew her on sight. The place came to a standstill at 5 a.m. It was clear that the terrifyingly long reach of Hollywood extends even to the Gobi desert, where presumably pirated copies of the Fast & Furious movies light up a thousand gers on winter nights.

On the long drive down to the desert town of Dalanzadgad, Michelle asked me if I had ever thought of setting a novel there, but I had to wave off the idea, saying: “I only just got here.” And in reality it never crossed my mind. Years later, it did cross my mind but alas to little effect. I was, in fact, fascinated most of all during that trip by Jalsa himself: a Kalmyk immigrant raised in New Jersey by illiterate parents, a hard-living self-made construction millionaire who had fought his way up through a Mafia-dominated industry, often with his fists. As well as being a leading conserver of snow leopards in the Gurvan mountains (he was a close friend of the late Peter Matthiessen, the nature writer), Jalsa is a high roller at Las Vegas casinos who regularly procures gifted cases of elite wines from the casino bosses. We became close friends almost at first contact.

On the same tiring drive during a solo visit the year after, Jalsa announced that we would be stopping to set up a trestle table on a mountain-top to drink four bottles of Pétrus. While his staff did this, I noticed four fetlocks standing by the road divested of the rest of the horse. Jalsa sighed. The zug, the winter wind, froze the horses solid and the wolves ate them chilled. We climbed the mountain carrying one of the wine bottles and on the way he dropped it, causing it to smash into pieces. There was no visible reaction on his part save a shrug. And so we sat in the sun on the mountain sucking $15,000 worth of drenched stones.

Over two years I wrote four drafts of different versions of the same story, which was inspired by a single dream I had had out in the Gobi desert. I had been sleeping next to the ger stove when I felt a large dog sniffing around my tent. I half woke and thought that it might be a wolf. Then, asleep once more, I had a dream about a seven-year-old girl disassembling a Rubik’s Cube with her mind, causing the pieces to float and tumble in the air in front of her. It must have come from somewhere, perhaps a film I’d seen. But I couldn’t remember where. A shaman, a possessed little girl, an inadvertent sin committed by her parents. The novel was a flop, as I suppose most trial novels are, but the wasted time and effort were so infuriating that I kept at it until the failure was so obvious that I had to force myself to desist. So I set it aside and moved on to other flops.

I suppose Mongolia’s relentless landscapes had worked their way into my subconscious for good. My mother always used to say: “Why don’t you write a nice love story here at home and make some money for a change?” She had acumen but I was now obsessed with the Gobi. I had the story, about a hunting party of three men chasing Gobi ibex, but I could not find the voice for it. Six years went by before I decided to try it out again, but this time not as a novel but as a script. It was a new form to me, but then if you don’t try new forms you never find out how talentless you might be at them. Over the last new year holiday I sketched out the script version of the story now called Solstice. Because I had been mashing these characters and the plot together for years the actual writing was a kind of free-flow. It wasn’t a working script, though — more like a pared-down version of an over-assembled novel. I gave it to John Michael McDonagh, the director of The Forgiven, based on my novel, hoping for a scathing bit of advice. I got that, of course, but the next question was: “So when are we going to Mongolia to do the recce?” Rather kindly, he offered to co-write the script so that actors could actually read it.

Jalsa had contracted Covid and so he could not join us a month later at the Shangri-La hotel in Ulaanbaatar. John came with Lizzie Eves, his producer, and we made a naive troika in the post-Covid, Ukraine-war era of Mongolia. Mongolia of course has a long and porous border with Russia. The place was packed with young Russian men. We’d see them at the bar or the restaurants, moody and tattooed, lost in a sort of mental wilderness. We flew to Dalanzadgad on a chartered plane and spent our days driving Land Cruisers to the remote valleys featured in the script and then, in the chilly and clear evenings, sitting around pit fires by neolithic nomad tombs and drinking for hours. I realized for the umpteenth time that my mother was wrong and that for some unfathomable reason these are the places where I am mentally at home. And sitting there among the tombs, almost anyone is bound to wonder about the unknown nomads who have lain there for 7,000 years undisturbed. The dead, and also the little petroglyphs that used to lie everywhere around them before tourists and locals stole them: prehistoric images of suns and moons, naked hunters and long-horned ibex. Those too must have lain silently in my unconscious for all those years, waiting for haphazard resurrection as a film.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.