When they looked back, indigenous historians remembered how the fall of the Aztec empire to Hernán Cortés had been prefigured by terrifying omens and portents. The central valley had been plagued by comets, eclipses and supernatural storms. The previous emperor, Ahuitzótl, died after hitting his head on a lintel. A strange woman stalked the streets of Tenochtitlán, the capital, at night, crying “O my sons! We are about to perish.”

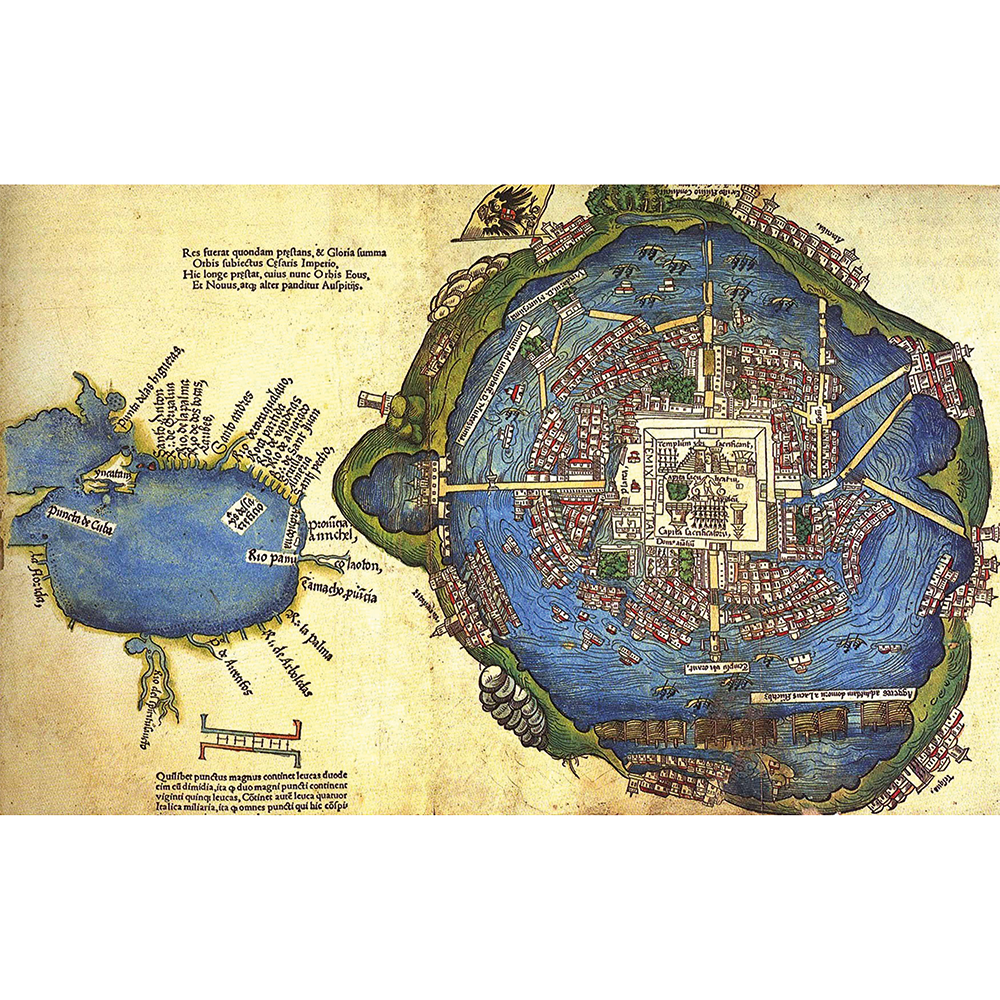

But there were other signs that might have been heeded, too. The empire itself was only a few decades old when Cortés arrived in 1519. It was a patchwork of rebellious territories and city states, surrounded by yet more hostile peoples. Tenochtitlán fell after a three-month siege in 1521. It was the Aztecs’ many local enemies that sealed the empire’s fate; Cortés proved better at negotiating competing political realities than many of his successors. At the beginning of that year, he had fewer than 600 of his own men under his command. Thanks to indigenous support, however, he had at his disposal more than 100,000 troops.

As Paul Gillingham makes clear in his magnificent new history of post-conquest Mexico, this fractious relationship between the margins and the center, the governed and the governing, would prove a surprisingly consistent feature of Mexican politics over the centuries. Something of this tension is reflected in the book’s structure: a strong narrative is interspersed with chapters approaching it from different thematic perspectives that reflect some of the country’s many contradictions.

New Spain, as the territory was called, would be a viceroyalty – a semi-autonomous kingdom – not a colony. Its autonomy was amplified by imperial indifference: “I have had no reply [to my letters],” Luis de Velasco, the second viceroy, wrote to Charles V in 1553. “It is two-and-a-half years since I wrote the first of them.” The indifference was often mutual. There was a diplomatic, if paradoxical, formula for evading unpalatable edicts: obedezco pero no cumplo (“I obey, but I won’t do it”).

Stubbornness, the persistence of difference, is another recurrent theme; Gillingham stresses continuity as much as change. Old boundaries and family-based political structures remained largely in place. The elites that most indigenous people dealt with were their own from the pre-conquest world. The Montezuma family held power in Mexico City into the 1620s; a century later, one of them, the count of Montezuma, would be the last Habsburg viceroy.

Nevertheless, the Spanish did bring profound disruption. New diseases – smallpox, typhoid, malaria, yellow fever and more – caused devastation. “They died in heaps, like bedbugs,” the Franciscan friar Motolinía reported of the arrival of smallpox in 1520. Two 16th-century outbreaks of enteric fever, a kind of typhoid, reduced the population of Texcoco from 15,000 to 600. The bishop of Oaxaca reported that in 20 years it killed 90 percent of his flock. Quarantine was one of the few available means of halting disease. The Spanish policy of congregación was its opposite: villagers were driven into towns where Christianity was easier to impose and people were easier to tax and control.

Control wasn’t easy. Riots were common: Gillingham records 140 of them in central Mexico and Oaxaca alone between 1680 and 1811. The greatest, in Mexico City, in June 1692, began with the death of a pregnant woman in a hungry crowd outside the city’s grain exchange. Government buildings went up in flames, including the viceroy’s palace and the mint. There were moments of humor – “Shoot! Shoot!” one protester shouted. “And if you have no musket ball, hurl tomatoes!” – but 12 rioters were either hanged or beheaded. This was the exception, however. Reprisals were rare. Bargains were usually struck and order restored. Riots, Gillingham suggests, were typically “counterintuitive solutions to conflict.”

Gillingham’s is first and foremost a political and economic history, and he is keen to show Mexico’s place on the world stage. First discovered in 1546, Mexican silver revolutionized the global economy, he argues. It flooded Europe. At least a third of it ended up in Asia, paying for silk and spices, tea and cotton. It also fueled urban growth in Mexico, making it “the world’s first wholly multicultural place.” To New Spain’s 160 ethnic groups were added some 150,000 people of African descent by the mid-17th century, together with traders and migrants from across Europe and Asia.

The Spanish fought a long, futile taxonomic battle to demarcate the population along racial lines. An entire genre of painting – the pinturas de castas, showing 16 different Mexican racial types – was invented. But the enslavement of Indians was illegal from 1542. Those who sued their owners usually won. In 1549, two slaves named Pedro and Luisa sued the conquistador Nuño de Guzmán – notorious for torture, enslavement and slaughter – and secured both freedom and substantial compensation. Indians proved enthusiastic litigants: one judge complained of endless opportunistic lawsuits, “Indians against Indians… subjects against lords… towns against towns.”

In 1810, two years after Napoleon placed his own brother on the Spanish throne, a parish priest in an obscure northern town launched a rebellion, ringing his church bell and shouting, “Death to the Spaniards! Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!” It turned into a war. Independence came in August 1821. But it was only the beginning of Mexico’s troubles: the government changed hands 48 times in the next 34 years.

The country’s elites became addicted to a distinctively Mexican form of low-fat coup called a pronunciamiento – Gillingham calls them “choreographed rituals” of revolt. Like the riots, they were more bargaining mechanism than revolutionary moment. General Santa Anna, intermittently the country’s president, specialized in them. He launched one in 1822 to reopen Congress and another in 1835 to close it. “He was very good at getting power,” Gillingham notes, “and very bad at exercising it.” The century also saw the beginning of Mexico’s difficulties with its increasingly powerful neighbor. “So far from God, so close to the United States,” the cliché ran. Texas seceded. The US invaded and took California, Utah and much else besides. The French put another Habsburg on the throne; Emperor Maximilian lasted three years before he was executed by Benito Juárez in 1867. His death was a watershed: between them, Júarez and a successor, Porfirio Díaz, would rule the country for more than 50 years.

Mexico modernized fast, helped by foreign money: half of all US overseas investment went into Mexico. The country’s GDP trebled, but economic links to the US proved a double-edged sword. When the US went into recession in 1907, Mexico followed. Díaz, nearing 80, promised to allow free elections in 1910. Then he changed his mind.

Guerrilla warfare erupted in the always-fractious north. The revolution lasted a decade. It cost close to one-and-a-half million lives – Gillingham calls it “the greatest mass dying in Latin America since the conquest” – and became a self-perpetuating cycle of violence. “La Revolución es la Revolución,” the saying went; a rhetorical shrug of the shoulders. Gillingham places the death toll in a contemporary global context. It is dwarfed by the collective dead of Ypres, the Somme and other such battles.

A further civil war erupted in the 1920s between the government and the Catholic Cristeros; civil war, a contemporary wrote bitterly, was “Mexico’s national sport.” Another was assassination.

Serious land reform arrived in the 1930s when the government redistributed nearly half of Mexico’s cultivable land – some 46 million acres. Lázaro Cárdenas, the president, hoped to “Mexicanize the indio,” the old dream at the heart of Mexican history. But there were always too many Mexicos, each as proud and independent as any other.

From 1938 until 2000, the country was a one-party state – sometimes a dictablanda, a soft dictatorship with elements of both democracy and autocracy, but latterly unambiguously dictatorial.

The October 1968 massacre of dozens, perhaps hundreds, of protesting students in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco district was a particular low. The government was in the early years of a guerra sucia, a “dirty war,” against some 40 different guerrilla groups nationwide. Suspects were disposed of in canvas sacks dropped from low-flying planes over the Pacific. How many isn’t known, but “the regime clearly killed thousands.” As ever, there are contradictions: this all coincided with 1,000 percent increases in health and welfare budgets; a million new homes were built for the country’s poor.

Gillingham’s account of Mexico’s history since its return to democracy in 2000 is dominated by the war against the drug cartels, which has many of the hallmarks of a full-blown civil war. It’s another facet of the country’s complex relationship with America. Mexico’s drug use is low by global standards; the cartels exist to feed US demand. By 2020, 200,000 Mexicans had been killed and a similar number had become refugees. Migration is another constant. The country’s first female president, Claudia Sheinbaum, elected last year, has troubles to confront.

But what a history her country has, and Gillingham’s account of it is a tour de force. If it’s easy for critics to focus on Mexico’s long struggle with internal violence, we might also think more about its enduring resilience and endless capacity for negotiating peace and stability – however contested – from apparent chaos. There is always cause for hope, however dark the omens. There are indeed many Mexicos; but there is also only one.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 8, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply