When John F. Kennedy was dating Jacqueline Bouvier, he gave her two books. One was Pilgrim’s Way (1940) a memoir by the British spy and author John Buchan. The other was The Young Melbourne (1939) by Lord David Cecil, which describes the raffish exploits and political intrigues of a Whig aristocrat, and later prime minister, in the early 19th century. Quite what Jackie thought of this is unrecorded.

Later President Kennedy told Life magazine what his favorite books were. Both of the titles above were in this proto-listicle, along with works about Byron, John C. Calhoun, Talleyrand and Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of The Roman Empire. Famously, this list popularized Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, with Kennedy such a fan that he invited Fleming to dine at the White House.

America had always been a republic of letters, but the years immediately before, during and after the Kennedy era were one of the peaks. After the war New York intellectuals and writers, clustered around different magazines and journals, were finally on the same footing as their equivalents in Paris and London. If anything they were even more glamorous and influential. Writers were deferred to, gossiped about, televised. Gore Vidal could be found writing novels and lurking around the West Wing. Norman Mailer could get away with stabbing his wife. The most beautiful woman in the world married a playwright who had probably never done a sit up in his life. Saul Bellow, in 1964, could sell 142,000 copies of his cerebral novel Herzog in hardback. In 1969 Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint appeared. This novel about a pre-Pornhub sex maniac sold 400,000 copies in its first 12 months. Books were important; they drove national conversations, they were a place you could go to find out what was going on in the culture at large. Books mattered to women, and to men.

Today reading is a shrunken pursuit, but particularly for men. Around 38 percent of men read at the lowest proficiency levels, and in 2017, 32 percent of men didn’t report reading a book at all. A gender gap in reading emerges in the data early on and is never closed. By adulthood women outbuy men in every category under which books are sold, aside from the recreational gore peddled in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Women listen to more audiobooks, attend more book clubs and join libraries in greater numbers. They make up something like 80 percent of fiction sales, which is why Ian McEwan once wrote ‘when women stop reading, the novel will be dead’. It’s why, in a rather more tendentious way, Karl Ove Knaussgård said that ‘reading is feminine’. Last week in the Times Literary Supplement, a reviewer claimed that ‘literary culture has been feminized to the point of strangulation’. If you were ever to investigate the culture around books on Instagram, you would see how true this is.

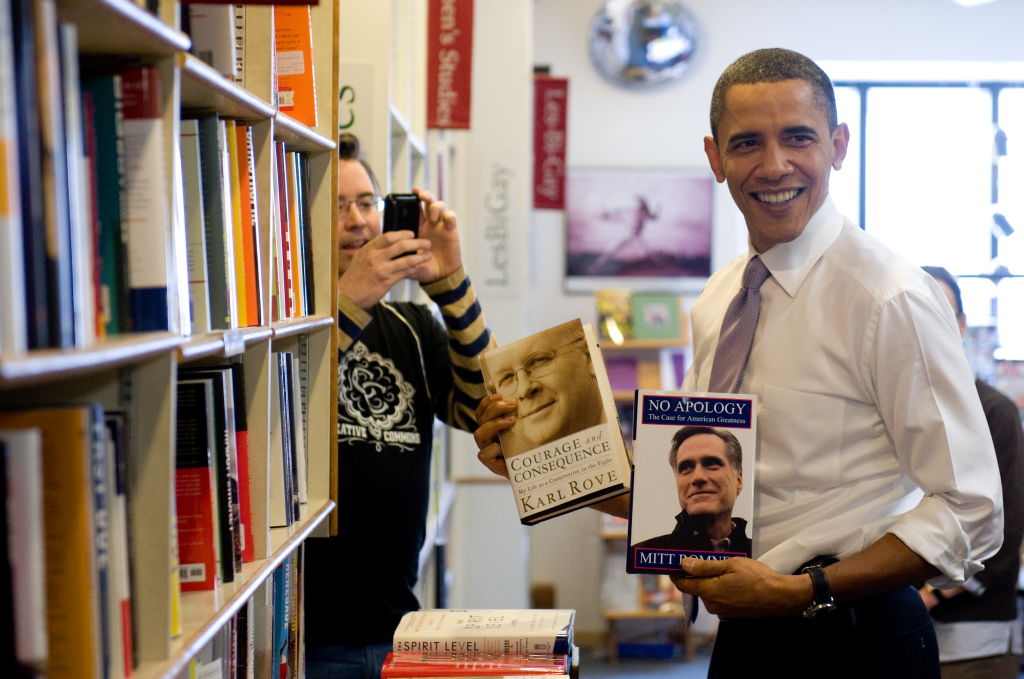

When famous or important men do talk about books in public, it always has a crimped, embarrassed quality to it. President Obama will often pop up with a list of his favorite books of the year. They’re always bland, impersonal and vaguely nutritious recommendations, as disappointing as receiving steamed broccoli when you’re dreaming of rare fillet steak. Kennedy’s favorites in 1961 have a singular flavor, and are clearly the harvest of personal inquiry. Obama’s could be culled from the book pages of any center-left publication in the Western world. Even more tragic was the book chat of Pete Buttigieg and Beto O’Rourke as they floundered around for our amusement last year. Both candidates picked out James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) as a treasured text. While this was totally on brand for each of them (boring erudition; campus conventionality) what baffled was how they managed to combine affectation with shame. Trying to explain the merits of Ulysses without sounding like a nerd, Buttigieg said it was a ‘democratic’ novel, which is a word made admirable when applied to matters of government, and useless when used to describe the refined and singular trajectory of a work of art.

One of the few men with a large audience to talk openly about books to other men was poor Dr. Jordan Peterson. Peterson advised reading a macho diet of gloomy heavy-hitters: Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Solzhenitsyn. He talked about these authors in a sustained, intense, fervid manner. For Peterson reading was a serious, high-stakes business. He discussed Crime and Punishment in the same way that four-star generals might discuss a complicated flanking maneuver involving thousands of soldiers, tanks and artillery pieces. How did the literary establishment react to this bold experiment in telling boys to read? Because Peterson also had some problems with speech laws and the gender pay gap, he took the full bombardment, up to and including the New York Review of Books calling him a fascist. Today Peterson lives in Russia, where he cannot recommend any books to young men, or anyone else. Occasionally he can be glimpsed on Instagram, forlornly driving remote controlled cars around a swimming pool, with all the frazzled dignity of a rejected prophet.

None of this explains why men don’t read as much as they used to. The temptation would be to lambast contemporary letters. How many novels need to be published about young Irish women who aren’t sure if they’re lesbians or not? How many artless poetry collections need to be dredged from brackish online ponds? How many intergenerational family sagas need to be set in geopolitically marginal zones? The publisher’s catalogues are full of technically competent, accomplished work that is also tame, literal and barren. But then again, if more fiction and poetry was published that made some kind of concession to the common tastes and interests of men (whatever those are), would more men read? I don’t think so.

***

Get three months’ free access to The Spectator USA website —

then just $3.99/month. Subscribe here

***

Lockdown has been more illustrative of this gender gap in reading than any event I can remember. Common concerns about health and job security aside, I’ve seen a lot of women decide that these are the weeks to finally read Anna Karenina and a lot of men decide that this is the time to shave their heads and fully embrace a pod life of video games, pornography and Twitter feuding. That’s the most obvious, and obviously correct answer to why men don’t read anymore. All of the attention and energy that might be given to careful reading has migrated online.

George Will lamented this erosion of ‘deep literacy’ the other day, without bothering to suggest any way it could be halted. That’s because deep literacy will not be making a comeback under online conditions. Many men won’t even realize it’s gone.