I was once at a terrific Shabbat dinner where late in the evening one of the other guests suddenly said: “OK, who’s got the best Holocaust joke?” Even people who know something about Jewish humor might be surprised by this.

I said that one Holocaust-related joke I knew was the story from the 1970s of the Monty Python crew being invited to Germany to film a television series there. The Germans had called the Pythons to say that of course they had no humor of their own in Germany and would like to import some. The Pythons agreed, arrived in Munich and were promptly taken to Dachau. In retrospect, this must have been some kind of signal from their hosts that they were accepting of their history and wanted there to be no awkwardness.

For one reason or another, by the time the cars filled with the Pythons and their colleagues pulled up to the gates, they were informed by the guard that the camp was closed for the day. Some pleading commenced, including an explanation of how far their guests had come, when suddenly Graham Chapman, who had been quietly drinking gin in the back of the car throughout the journey suddenly shouted: “Tell them we’re Jewish.”

Of course this is really a Python joke, more than it is a Holocaust joke. To the extent that they exist, Jewish jokes on the Shoah have a very dark, even theological, feel. Here is one. Two men both killed in the Holocaust are in heaven. They haven’t seen each other since the camps and they are laughing at something that happened there. Indeed they are laughing so much that they attract the attention of God, who is passing by. “My children, my children,” says God. “How could you laugh at such things?” One of the Jews stops, turns to God and says: “I guess you had to be there.”

I heard a similar one in Israel during the second intifada, when suicide bombings were happening daily. To understand this joke, you have to understand that it is fairly common for schoolchildren in Israel to visit the camps in Europe at some stage in their education. Anyway, a bomb goes off in a famous pizzeria in Tel Aviv and one mother in the city calls another. “Efrat, I just heard the news. Are you and the children all right?” “Yes, thank goodness, I’m OK.” “And the children?” “Oh yes — they’re fine. They’re in Auschwitz today.”

That joke never makes me laugh out loud but like the other one I admire the punch it packs, while also providing one of the tasks that, psychologically speaking, jokes are meant to perform. Which is that they are in part an attempt to confront the horrors of the world and help us through them. Which brings me to Jimmy Carr.

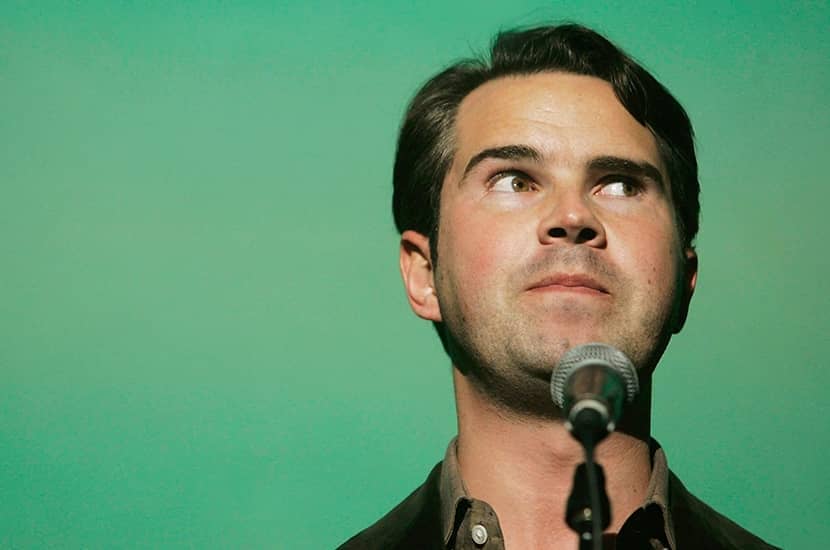

Carr is one of the comedians I dislike the most, for reasons too numerous to go into here. But I have always had a very easy means of dealing with this dislike — which is that I have never paid to see him perform live, have never watched any of his shows straight through and have almost never laughed at anything he has said. I slightly admire his deadpan style of delivery, but his idea of what is and is not fit for humor doesn’t agree with me. He has that type of humor where people don’t really laugh, but rather gasp performatively and then laugh, as though to say: “Naughty Jimmy, I can’t believe you just said that.” Before he turned woke, the Scottish comic Frankie Boyle was like that too. Never really funny, just meant to make you gasp and then fake-laugh. There is some evidence that Carr too has been turning woke. But it used to be all jokes about cripples, retards and the like. Not really my thing.

Now Carr is in trouble, with Britain’s culture secretary Nadine Dorries among others, because he told a Holocaust joke. His latest Netflix special (called His Dark Material) includes a knowingly “edgy” passage, which I will not spare you. “When people talk about the Holocaust, they talk about the tragedy and horror of six million Jewish lives being lost to the Nazi war machine. But they never mention the thousands of gypsies that were killed by the Nazis. No one ever wants to talk about that, because no one ever wants to talk about the positives.”

This went down very well indeed with the live audience, who roared with laughter, clapped and in some cases whistled. Personally, I think that even in its context the joke is cruel and unwitty. I thought something very near to that watching another comedy special some time ago, when the excellent Ricky Gervais made a tangential joke about Anne Frank. On that occasion it felt to me like Gervais just about got away with it. That is part of his genius. But I also thought: “I’m not sure you’ve earned the right to joke about that.” You have to be a comedian really gnarled and long in the tooth to try something like that. Even then, as with the jokes above, you probably have to be Jewish, or Romany, and be making some deeper point.

But this is a matter of taste. I watch everything Gervais does, and try to avoid anything Carr does. And that, dear reader (and ministers, if you happen to be reading), is what a free society is like. We all of us express our approval and disapproval of things every day in acts of taste like turning off or turning on.

There are many things worse than an ugly joke. Among them is the idea of UK government ministers like Dorries and Sajid Javid condemning the jokes of comedians or calling for action to be taken against them. Let alone the Scottish National Party councillor who has called not only for Carr but also his audience to be prosecuted for hate speech.

As with the UK’s online safety bill, which seeks to protect internet users from unpleasant content, this is just a displacement activity for politicians who seem to be copying a section of the public in searching for things to be outraged about. They should be warned. It is the easiest thing imaginable to hang the jester. But it never solved the problems of any court, nor improved any society over which that court was struggling to govern.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.