Copper has a nickname in the commodities market. It’s known as “Doctor Copper” because it’s so deeply integrated into the physical fabric of our lives and all the technology we depend on that its price reflects the health of the economy. “Gold is money, everything else is credit,” said J.P. Morgan more than a century ago. But copper is more than money. It’s modern human life. It is used in every corner of our technology, from houses to windfarms to warehouses. Which is why I think, while everyone’s still obsessing about gold, it’s worth taking a look at copper.

Since the global financial crisis in 2008, stock markets may have reached new highs but the physical world of construction, infrastructure and manufacturing has never quite regained its old growth rate. Western consumers borrowed, policymakers stimulated, AI and tech shares soared, but factories, grids and cities grew slowly. And copper demand over the past 15 years (at 1.9 percent) was below the average of 3 percent annual growth seen since 1950.

At the same time, a wave of new mine supply hit the market. Pre-crash, the West raised money for mines thanks to the low cost of capital. Post-crash, China has led the way with new mines in Ecuador, Peru and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This has resulted in a period where supply consistently ran ahead of demand. As a consequence, copper priced in real money (expressed in units of gold) has been on a long downward trend. Despite all the chatter about battery metals and nominally rising prices, copper has been in a bear market and is 60 percent lower in real terms than it was 25 years ago.

The most obvious driver for the coming bull market in copper is our insatiable appetite for electricity and all things electrical. The world’s largest mining company, BHP, estimates that as recently as 2021, about 92 percent of copper demand still came from traditional sectors such as construction, old-fashioned power systems and industrial machinery. Only about 7 percent was explicitly tied to energy transition uses (EVs, renewables, grid upgrades), and 1 percent to digital tech and data. This is changing fast – just look around you.

The world is electrifying at a breakneck pace. In March, the International Energy Agency (IEA) published its “global energy review of 2024” and noted that, although global energy demand grew by 2.2 percent in 2024 (faster than the average rate over the past decade), electricity demand surged by 4.3 percent. And with electricity demand, you can assume copper demand, too.

EV sales continue to rise globally, and of course each electric vehicle requires three to four times more copper than an internal combustion car: 80-90 kg vs. 23-24 kg. Wind turbines are still popping up. Every single wind turbine uses two to three tons of copper per megawatt of capacity in the turbine itself – but you can double that to include connecting cables for on-shore windfarms, and more again for off-shore installations. Diffuse energy collection systems such as solar panels also require vast amounts of copper cabling. Don’t forget copper use in grid-scale batteries and in high-speed charging infrastructure. And then look at aging grids from the US to Europe to Asia, which need massive upgrades. And then look at your own personal habits and what you have bought recently. Smart devices, automation, the internet of things. The battery in every chargeable device you use is 10 to 15 percent copper by weight. Copper, copper, everywhere.

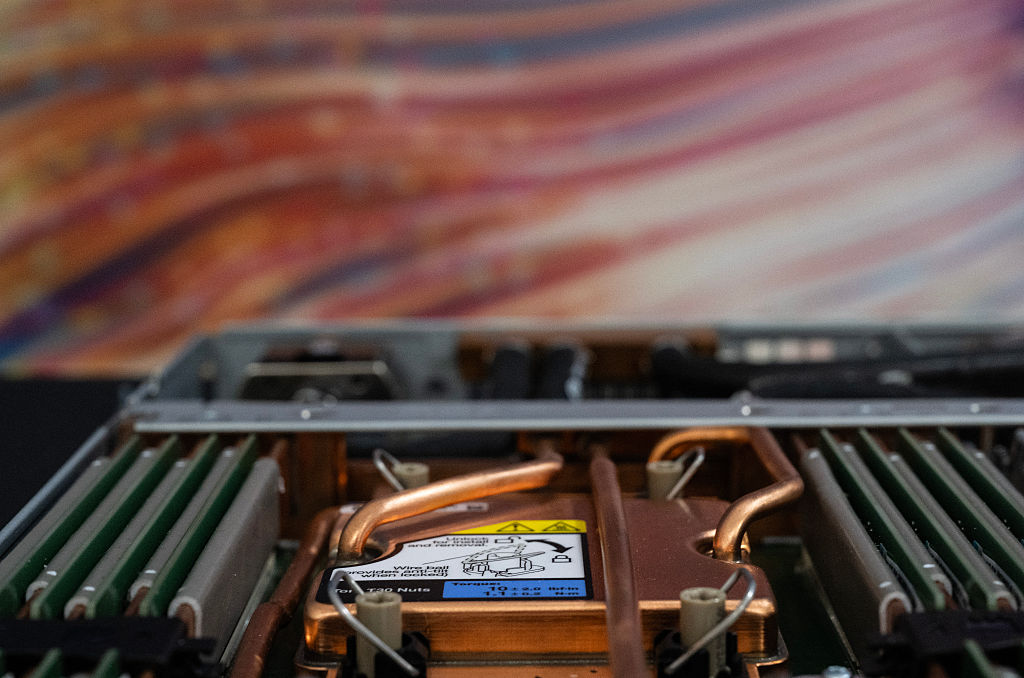

As if that isn’t enough, throw in the big one: AI and data centers. The AI boom isn’t just virtual, it’s physical too. Every data center needs transformers, cooling, power-switching equipment and miles of copper cable. The growth has barely started and our future world is being built on electricity – and on copper.

The IEA now forecasts explosive growth in copper demand from electrification through the 2020s and 2030s. Goldman Sachs, BHP, Wood Mackenzie, UBS and others independently say the same thing: we are entering a structural shortage. The “old copper” market is forecast to shrink to 60 percent of the demand pull, with new sectors likely to comprise 40 percent of the market within 15 years. And remember that “old copper” demand is still growing at 2 percent annually, which in a 24-million-ton annual market is 480,000 tons of new copper demand every year.

And herein lies the problem. Copper mining is an incredibly large and mature industry. Most of the easy deposits have already been mined and the global mined average grade is now around 0.5 percent Cu. Future deposits are likely to be lower grade, harder to access, deeper and more complex. Water is a major issue. Either there is too much, with mines flooded this year in Indonesia and the DRC; or there is too little, with large deposits above 4,000 meters looking for a water solution in the Andean deserts of Argentina and Chile.

Now consider much tighter environmental regulation and granting of permits and it is no surprise that the average development timeline for a copper project to advance from discovery to production is 18 years. This is not an industry that can be turned on quickly – unlike an immature or small-tonnage commodity such as lithium. A large copper deposit in the discovery phase today is unlikely to be in production until 2043.

Furthermore, local opposition is rising. Social license to operate and indigenous rights are increasingly restrictive factors in Australia, Canada, Ecuador and Peru. And apart from a few established mining hot-spots, Europe is essentially off-limits to any meaningful mining venture due to high power costs and a fundamentally anti-mining, eco-socialist mindset. Even the US, with Trump’s tariffs and exhortations to redomicile copper production, is challenged. To produce large quantities of refined copper you need abundant smelting capacity, and America is currently exporting copper minerals for processing abroad.

Does anyone want to take a wild guess where the newest, most efficient, lowest-cost smelters have been built? Smelters so efficient and with so much capacity that they render most other new smelter proposals unviable. Of course it is China, with its 60 percent coal-fired, low-cost power grid. Fierce competition among smelters and refineries in China has translated into record low margins for smelters and refineries around the world. Two state-run smelters have closed in Chile since 2023, and in Australia, Glencore’s Mount Isa smelter, which has operated in the town for almost 100 years, is being prepared for closure. As Glencore says, “The future of our Mount Isa copper smelter and Townsville refinery is currently under review, as global market shifts and reduced copper volumes challenge the sustainability of these assets.”

At one point in September, Chinese smelters were actually paying suppliers of copper mineral (concentrate) to deliver material to them, when normally miners pay for the privilege. Essentially the emergence of the Chinese processing capacity is yet another indication of China’s dominance in primary materials and manufacturing. (When will liberal democracy governments actually notice that economic and industrial activity depends on low-cost energy, which in turn relies on a high proportion of reliable, low-cost spinning generation such as coal, gas, or nuclear?)

One of the real challenges for the copper industry is that even expanding production from existing mines is proving to be extremely difficult. Mining companies are having to spend large sums of capital on existing mines just to stand still, let alone grow production. Look at Chile, the world’s largest copper producer. The Chilean Copper Commission, Cochilco, estimates that investment of $83 billion will be spent on mining in-country to 2033, mostly in the copper sector and that production will only incrementally rise from 5.3 million tons last year to 5.5 million tons in 2033.

Separately, BHP runs the world’s largest copper mine, Escondida, in Chile. And in its August presentation, BHP estimated that an investment of about $5 billion in Escondida would take production out to 2031 with only a drop of about 20 percent to one million tons annually. The world needs a new Escondida every other year, and even this huge mine is struggling to keep up. Overall, BHP forecasts no growth in production from its Chilean operations from 2031 to 2040.

Staying in Chile, one of the most cautionary tales of recent times is Teck’s expansion of the Quebrada Blanca mine in a project called QB2. Originally estimated to cost$4.7 billion (in 2016) the project was updated in 2023 to a forecast of $8.8 billion, and now all bets are off. Ten billion, anyone? Even worse, during Teck’s acquisition by Anglo American, Teck lowered production guidance from the mine. Problems with downtime, throughput limitations and higher unit costs mean that production forecasts of 230,000 to 310,000 tons of copper annually for the next few years have been reduced to 170,000 to 255,000 tons. Do you see the trend? Cost estimates are up, production estimates are down. Copper mines are major infrastructure projects that are increasingly difficult to deliver in a modern world.

To make matters worse, the fragility of mine supply is currently center stage as several large operations have come unstuck. Flooding in the DRC and Indonesia, seismic activity in Chile, political shutdowns in Panama and social unrest in Peru have removed roughly 800,000 tons of annual supply from the market. And although much of it should come back on stream during 2026 and 2027, it is too little, too late.

Governments are waking up, but what can they do? The US and EU have added copper to their “critical minerals” lists, which seems more a statement of the obvious than a policy plan. Within five years, the world may need an additional six or seven million tons of copper annually that simply does not exist in any mine plan or construction schedule today.

The slow-motion capital blow-out of the QB2 mine expansion is causing the large mining companies to baulk at committing to a new mine build. While it may be easier for companies to buy production through mergers and acquisition, copper prices will have to be much, much higher to stimulate the construction decisions on the new big mines that are needed to fill the supply gap.

In short, the fundamentals of supply and demand dictate that the copper price has to re-rate. The copper industry is so large and so mature, with such long development timelines, that it is relatively price insensitive. Copper supply is capital and time constrained. The nature of copper demand has fundamentally changed: AI and electrification is turbo-charging copper use.

The copper crunch is coming, prices are going to rise far and fast, maybe two or three times higher than today’s prices. It is going to take a long time to get a meaningful supply response. Hold on tight: copper’s going for a ride.

Merlin Marr-Johnson is president and chief executive of Fitzroy Minerals.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 8, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply