A cold front blew in off the Florida Straits, sending waves over Havana’s famous corniche, the Malecón, and announcing what has traditionally been the end of the hurricane season. After 13 named storms, it seems as if the 2025 season finale was Hurricane Melissa, a humdinger. She paused south of Jamaica, getting herself into a lather, before killing 32 on that lovely island and causing at least $7 billion of damage.

Fortunately for Cuba to the north, Jamaica’s mountains plucked the murder from Melissa’s eye – but she still cut a devastating trail through this bigger island’s eastern reaches a day or so later.

As Cuba’s communist leadership donned military fatigues and began its traditional mobilization for such events, my phone lit up with messages from friends around the world. They had seen images of the vast, spiraling cloud, top-lit by lightning and imagined apocalypse.

But we, unlike many, were fine. Hurricanes are surprisingly localized. You really have to be within 50 miles of the eye to feel the full force and Cuba is huge, the same length as California. And its government is good at the immediate stuff. No fatalities were reported on the island.

But I appreciated the concern. If a Cuban city does take a direct hit, it will be calamitous. Storms that pass 50 miles away from you might be OK, but in the eye of the storm, even in well-prepared countries, the suffering can be terrible.

I’ve been sideswiped a couple of times, which was frightening enough. But pros such as my friend Patrick, who as a CNN correspondent is forever stepping into the path of tempests with names like Beryl or Dorian, says emerging after a direct hit is terrible. “You are greeted by scenes of damage so extensive as to be otherworldly,” he says. “Cars flung into trees, houses cleaved from their foundations, trees stripped of every leaf.”

Cuba’s long-term financial woes mean the island’s beautiful old cities are falling down, even in clement weather. Habaneros tend to walk in the middle of the street because of the danger of falling masonry. Last month, an entire house collapsed in the old town, killing a mother and son.

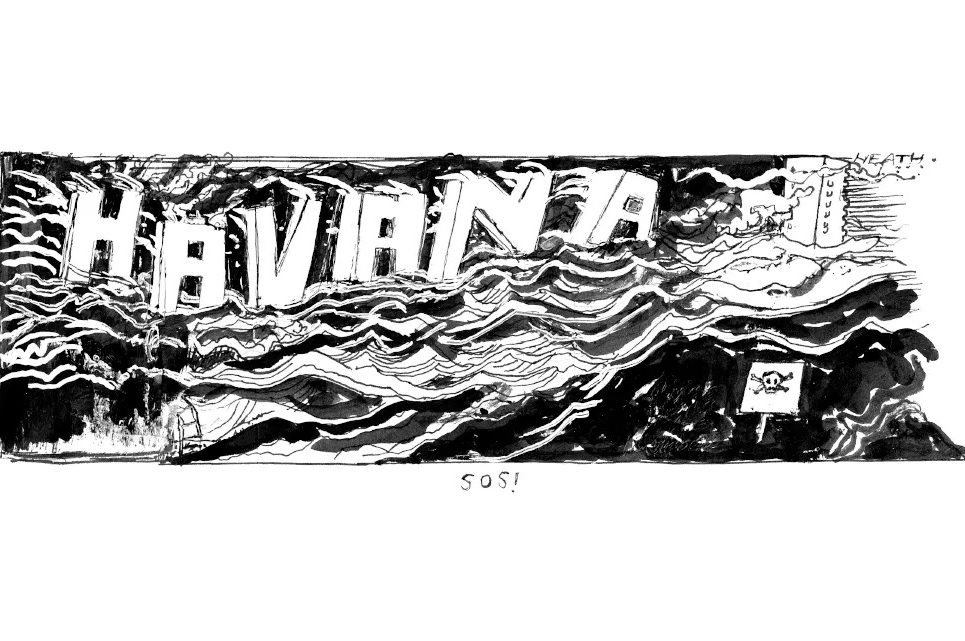

Any hurricane, let alone one the size of Melissa, would probably annihilate a Cuban city. Which would be a pity. Cuba’s capital has been a storied wonder for five centuries; a recent visitor reminded me that Norman Lewis once called Havana “the most beautiful city of the Americas.” A big storm has the power to bring that story to an end, along with untold lives.

So, we depend on luck. In summer I obsessively watch the National Hurricane Center’s website, tracking storms forming off Cape Verde which grow stronger as they head west. It feels like being a pin in a bowling alley, watching the ball coming down the lane and praying it will miss.

Cubans have developed a whole slew of coping mechanisms. First they turn to the sainted Dr. José Rubiera on the news. For many years the director of the National Forecasting Center, his mustachioed cool acts like a balm as he rationally describes a storm’s possible paths.

If a hurricane begins to get close, the Cuban authorities declare an estado mayor de la defensa civil and show off the advantage of being an authoritarian regime. In Jamaica in October, people refused to flee. One resident of Port Royal was quoted as saying the last time she took to a shelter, “females weren’t safe and to top it off, people stole our stuff.” In Cuba, by contrast, the residents had no choice. Some 735,000 people were moved whether they liked it or not. But they were safer.

Here in Havana, when hurricanes approach, an eerie calm takes over. People sweep their roofs of junk and stones or anything else that might shatter windows. Queues form for bread, often to the last minute. I once ran to the bakery with my brother-in-law as electricity transformers exploded above our heads. “Do we really need a loaf this much?” I remember shouting.

Afterwards, the unafflicted gather aid for the stricken. And then it’s the long road back once everyone has forgotten. My colleague Eileen recently returned with a convoy to the areas affected by Melissa. She tells me of a dam overflowing, washing away houses and livestock, of misery piled on misery.

Without money to rebuild, Cuba now carries the scars of past storms. One of my favorite places on the island is a village called Isabela de Sagua. In 2017, Hurricane Irma passed by, a terrible storm because she never touched land but instead sent the sea inland all along the coast. Isabela was all but washed away. There’s a restaurant there I like where boats arrive under sail (there isn’t a lot of gasoline at the moment) to unload fish, crab, oysters and lobster. The food costs pennies and tastes sublime. It feels like the restaurant at the end of the world.

But putting aside my suspect love for trauma tourism, that’s not great, is it? Such stoic tenacity from residents is not really enough. One day a hurricane is going to prove Cuba’s authorities inadequate. Nonetheless, for now, and until June next year, I will be able to sleep soundly, certain my family is not going to be wiped out by a storm with a silly name.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 8, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply