Cameron Crowe’s long-awaited memoir The Uncool can be read intertextually as the real Almost Famous. The Uncool is also about lush California summers, grief, the unwavering support of a mother, cool big sisters, and Almost Famous: The Musical, but when you peel back the pages like it’s a vintage magazine, there’s an elegiac aroma. This is a crinkled love letter to a deceased paramour; in this case, the beating heart of rock journalism. Crowe treats writers such as Lester Bangs (“my heart was almost all Lester Bangs”) and Danny Sugerman with devotional reverence that is as uncool or “problematic” in 2025 as learning about sex from your mom in a laundromat and writing about it. Crowe’s lack of cool thus becomes the book’s artistic frame.

“The personal tone of that embarrassing article [learning about sex from your mom in a laundromat] is now my favorite kind of writing. In fact, it’s the tone of this book,” writes Crowe, who acts as a fanboy chronicler timestamping each vignette. The book consists of a series of short diaristic entries with a concert review (e.g., Elton John at the Civil Theater, 1971), a snippet from a rock tour, a magazine profile, some sagacious advice from his mother, Alice, and interviews with some of the last rock stars.

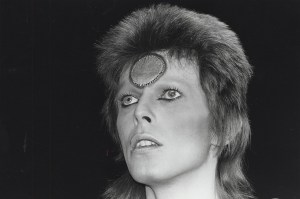

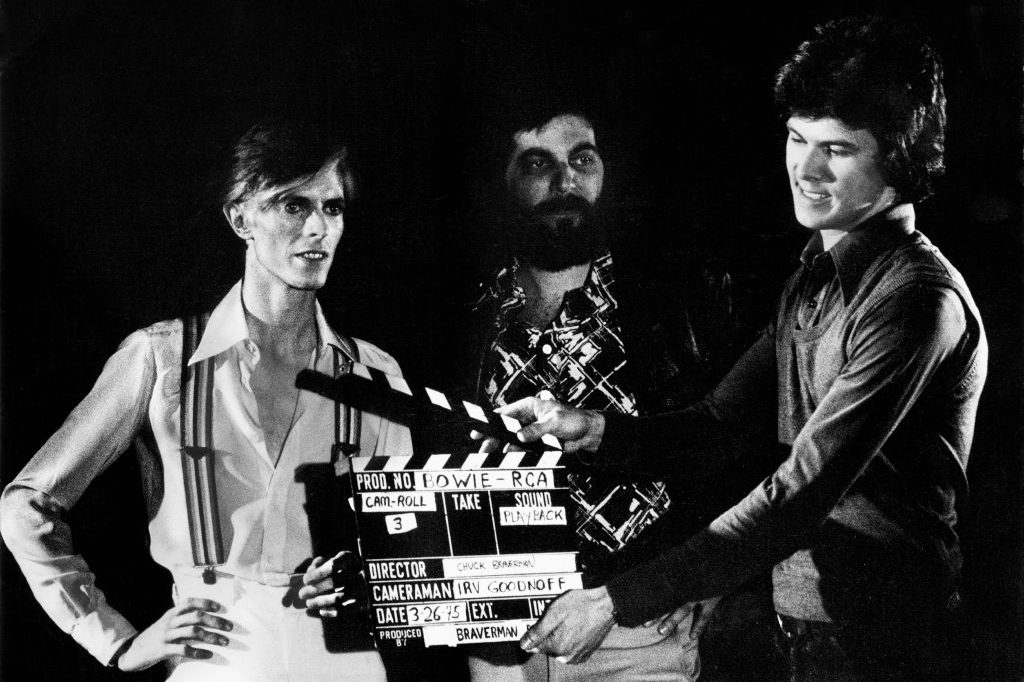

An example: it’s 1972 and Crowe is a shaggy-haired 16-year-old rock obsessive who wants to interview David Bowie, except Bowie doesn’t do interviews. A seasoned rock journalist (Sugerman) tells Crowe that they’re going to find Bowie and interview him. Crowe is uncool, and Bowie’s mystique is informed by the fact that he’s intensely and prodigiously cool, but Sugerman drags Crowe across the Sunset Strip on a quest to find Bowie. Crowe peers up at billboards plastered with rock album covers (now replaced by Skims adverts). They stop at Rodney’s English Disco (now an art gallery): “all mirrors” that shimmer with disco lights. “David was just here,” Rodney tells them; they also just missed Elvis.

They find Bowie at the Beverly Wilshire. “The most sought-after subject to every cassette-slinging rock writer” is gaunt and pale with red hair, deep in his Thin White Duke era. Bowie invites Crowe back to his room to play some records (bonding over a shared love of R&B and soul). Eight days later, Bowie calls Crowe at his parents’ house: “You can ask me whatever you want,” Bowie later tells him. “Hold up a mirror and show me what you see.” Crowe describes this as an “artistic challenge from David Bowie” when he was young, just “young enough to be honest.” The Uncool wants to be as honest as that teenager. That is its conceit and its artistic challenge.

The Bowie story is not a deleted scene from Almost Famous, which was conceived by Crowe as a coming-of-age story about a 15-year-old boy who convinces Rolling Stone (and his mother) to let him tour with Stillwater, a stand-in for the Allman Brothers: a band Crowe toured with when he was 16, an experience documented in the book in great detail. The memoir, like the semi-autobiographical film that precedes it, which Crowe has described as a love letter to family and music, is equally concerned with music and the feeling it conjures through memory, nostalgia, translation and the artistic challenge of being authentic in the commercialized world of corporate magazines.

Crowe’s essence isn’t cool or intellectual; it’s his ability to translate real experiences into shamelessly cringe (and relatable) pop storytelling that sings. The “Bangsian magic, wild and beer-stained and beautiful” was never Crowe’s beat. That’s why he’s still alive. “Danny [Sugerman] would indeed make his mark,” writes Crowe, “and he’d sadly check out early like his hero [Jim Morrison], but to my mom he was always just ‘the kid with the smelly feet.’” Crowe’s protective mother kept him from becoming another tragic footnote in the history of rock journalism.

The Uncool ably chronicles Crowe’s Almost Famous-coded moments and snippets including Bob Dylan waxing poetic about the 1960s, the “karate king” incarnation of Elvis, Jann Wenner handing Crowe a copy of Joan Didon’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem – “…if you want to be a real writer” – and Led Zeppelin hiding from female groupies at gay discos, which do not compute with our modern understanding of managed celebrity or PR-driven journalism.

I should have put “rock journalism” in scare quotes as its authenticity has been diluted into manufactured poses, exactly as Bangs had predicted. This brings me back to Crowe, who’s all heart and authenticity when he anchors the book with the voices of his loving parents. It culminates in a sustained note that summarizes Crowe’s nostalgia: “Nothing beats the sound of the human voice. I still hear my mom’s voice all the time. She’s still teaching.” Her voice – and the voices of rock’s past – are the things Crowe aims to preserve before there’s no one left alive to do so.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 8, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply